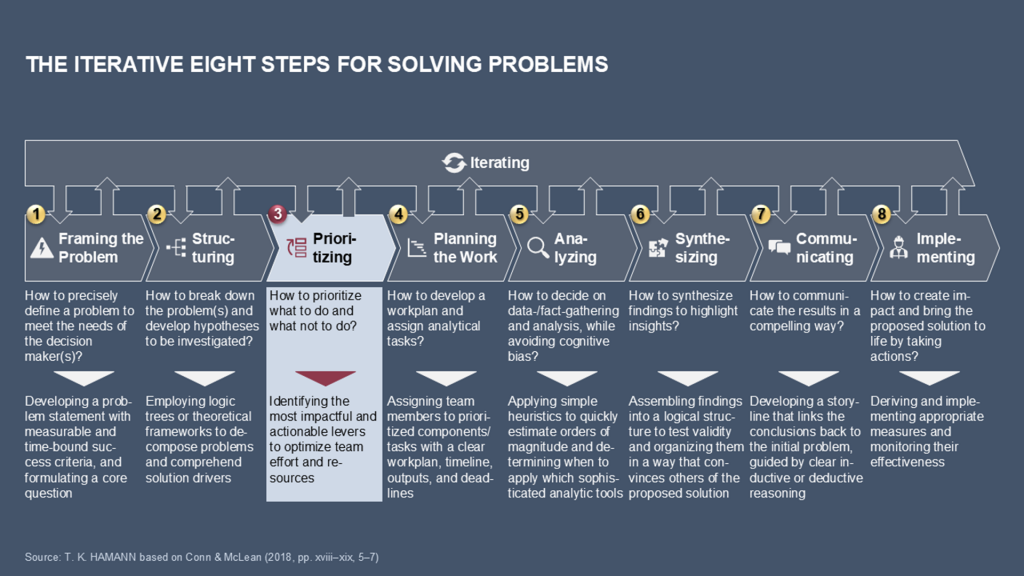

The Iterative Eight Steps for Solving Problems – Step 3: Prioritizing

Prioritizing is the third step in the Iterative Eight Steps for Solving Problems (see Exhibit 1). After framing and structuring a problem, teams often face a wide set of sub-questions, potential causes, and analytical paths. The challenge is clear: deciding where to focus first.

Unlike framing and structuring, which are expansive, prioritization is selective.

Prioritization is the deliberate process of choosing and ordering problem elements, hypotheses, or actions based on expected impact, feasibility, relevance, or urgency.

The purpose of prioritization is to direct limited time, energy, and resources toward areas that are most likely to create value while safely deferring or discarding less essential work. Thus, prioritization becomes the bridge between comprehensive thinking and focused execution. Without it, even the most elegant problem structure is just a map with too many roads and no clear route.

When done well, prioritization prevents wasted effort, analysis overload, and curiosity-driven detours. It transforms a broad problem space into a clear analytical agenda—a targeted set of questions and tasks that will most effectively drive toward a solution—ensuring faster learning, sharper insights, and stronger alignment with decision makers.

Importantly, prioritization is not a one-time event, but rather a dynamic process that must be revisited as new information emerges. Prioritization serves several interlinked functions:

- Focusing: Concentrating resources on what will deliver the greatest learning or impact.

- Filtering: Separating the signal—information or hypotheses directly relevant to solving the problem—from the noise, which adds little value.

- Scoping: Defining the depth and breadth of the analysis for each area to avoid overengineering or doing unnecessary work.

- Sequencing: Determining the most effective order of actions based on urgency, logical dependencies, and strategic importance.

These functions reinforce one another: a sharper focus improves filtering, and clearer sequencing refines scope.

A simple analogy is that structuring creates the full menu for a meal, while prioritizing decides which courses to serve, in what order, and in what portions. The goal is not to serve everything but rather to create the best possible dining experience with the right ingredients in the right sequence.

Ultimately, prioritization imposes strategic discipline on analytical ambition. It is the problem solver’s way of saying, “We know what matters, and we’re acting on it.”

1. Why Prioritizing Matters

1.1 Making the Best Use of a Limited Set of Resources

The first driver of prioritization is resource scarcity. No problem-solving team has unlimited resources, whether they are addressing a strategic transformation, operational turnaround, or customer experience redesign. Time, analytical capacity, stakeholder attention, decision-making bandwidth, and organizational energy are all finite and non-renewable in the context of a single project. Once spent, they cannot be reclaimed.

Resource constraints are limitations inherent to time, analytical capacity, data availability, decision-making attention, and organizational influence that determine how quickly, deeply, and effectively a problem can be addressed.

In theory, a problem can be examined from every angle. In practice, however, there are looming deadlines, incomplete data, impatient stakeholders, and limited team capacity. Prioritization is the strategic response to these constraints—a way to focus efforts on the areas that will have the greatest impact rather than scattering resources across many low-value avenues.

The temptation to “do it all” is strong, especially when leaders seek full visibility and certainty. However, spreading effort too thin slows analysis, dilutes insight, and weakens recommendations. Prioritization guards against this by making deliberate trade-offs early and confidently.

1.2 Creating Convergence for Value and Actionability

Not all aspects of a problem are equally important. Some are peripheral, some are difficult to influence, and some may be politically infeasible. Prioritization highlights the components most likely to generate insight, support key decisions, or produce meaningful results. Value and actionability become the guiding criteria.

Strong teams accept that trade-offs are inevitable. For instance, a minor logistics delay affecting only one facility for a short period may not merit deep investigation. However, if two regions account for 80 percent of delivery complaints, those areas deserve concentrated attention.

Imagine a leadership team investigating a struggling product line. The team’s analysis covers five areas: customer experience, pricing, supply chain, salesforce performance, and brand awareness. With only six weeks to deliver results, analyzing all five areas in depth would result in missed deadlines or shallow conclusions. Instead, the team focuses on customer experience and salesforce performance, both of which were flagged by early data as high-impact levers, while placing the others on a watch list. This approach ensures that energy flows toward high-leverage areas.

Convergence is the narrowing phase of problem solving in which a broad set of structured issues is reduced to a smaller set of high-priority areas for focused action.

1.3 Supporting Stakeholder Alignment

Prioritization also fosters stakeholder alignment. Rather than exhaustive coverage, executives and sponsors want actionable insights that support timely and confident decision making. A prioritization-driven agenda demonstrates that the team is focused on what matters most and can justify its choices.

Involving stakeholders in the prioritization process helps identify high-value levers, ensures feasibility, and increases buy-in. This collaboration bridges the gap between analytical logic and organizational reality.

1.4 Accelerating Learning and Sharpening Thinking

When applied early on, prioritization can speed up the learning process. By testing high-impact hypotheses first, teams can quickly validate or disprove key assumptions, refine their understanding, and adjust their approach as needed. This rapid feedback loop speeds insight and simplifies synthesis and communication because the storyline is already organized around the most critical factors.

1.5 Avoiding Common Pitfalls

Although the logic of prioritization is simple, executing it effectively can be challenging. Even experienced teams can fall into predictable traps, which are usually driven by cognitive bias, unclear communication, or organizational habits.

Prioritization pitfalls are predictable errors in deciding what to focus on which can lead to overcommitment, misallocation of resources, or pursuit of low-value activities.

1.5.1 Trying to Do Everything (Analysis Overload)

After creating a detailed logic tree or hypothesis map, teams may feel obligated to analyze every branch, which is akin to “boiling the ocean.” This results in an overly broad scope, analysis fatigue, and delayed progress. A related risk is analysis paralysis, which occurs when too many options or too much data stalls decision making.

Analysis paralysis occurs when an abundance of data, hypotheses, or choices prevents effective progress, usually due to a lack of prioritization or focus.

Solution: Treat structuring as creating options, not obligations. Use prioritization to narrow the scope to a few important branches, at least initially.

1.5.2 Deferring Prioritization Too Long

Some teams delay prioritization until more data arrives, waiting for the perfect information needed to make trade-offs. In fast-moving or complex situations, however, that moment rarely comes, resulting in diluted effort and lost focus.

Solution: Prioritize early based on working hypotheses, initial signals, and professional judgment. Treat these priorities as provisional and revise them as new evidence emerges.

1.5.3 Equating Interest with Importance

Teams may be tempted down rabbit holes by intriguing or novel aspects of a problem—analyses that are intellectually engaging but strategically irrelevant.

Solution: Anchor prioritization to impact. Use tools such as the impact-influence matrix (see Section 3.1) or back-of-the-envelope estimates (see Section 3.5) to determine if a branch is worth the effort. Ask: “If this is true, will it change our recommendation?”

2. Principles of Effective Prioritization

Effective prioritization is not just about moving quickly; it is about moving intentionally. In structured problem solving, the goal is to allocate limited resources toward issues that are the most important, actionable, and time-sensitive. This requires a deliberate mindset that constantly scans the problem landscape, evaluates what is truly important, and adjusts focus as circumstances change.

The principles of prioritization are foundational guidelines for determining where to focus efforts and ensuring that resources are directed toward the most impactful and actionable elements of a problem.

These principles help teams avoid two common pitfalls:

- Overanalysis: Spending excessive time and resources on low-value details.

- Misplaced effort: Pursuing work that is interesting but irrelevant to the decision at hand.

The principles below bridge the gap between the broad mapping of the structuring phase and the selective action of execution. They also lay the groundwork for the tools and techniques (see Section 3) and heuristics (see Section 4) that transform these concepts into practical, repeatable methods.

2.1 Focus on Value First: What Matters Most?

At the core of prioritization is a simple yet powerful question: “What will create the greatest value?” In this context, “value” refers to the potential of an issue, hypothesis, or task to meaningfully advance the desired outcome, whether it is reducing costs, growing revenue, mitigating risks, or achieving decision clarity.

Once a problem is structured, the resulting logic tree or map often reveal multiple hypotheses and potential paths. However, not all will contribute equally to performance outcomes. The challenge lies in identifying the “critical few”—the elements most likely to deliver meaningful results—while deferring, simplifying, or omitting the rest.

Focusing on value does not mean ignoring other aspects of the problem. Rather, it means allocating analytical, managerial, and organizational resources where they can deliver the greatest return.

This approach applies at every stage, from developing initial hypotheses to shaping the final recommendation.

Criteria for determining what matters: In most contexts, importance can be assessed using three lenses:

- Relevance: “Is it directly tied to the problem statement, stakeholder concerns, or core hypotheses?”

- Impact: “Will resolving it meaningfully shift performance, cost, risk, or opportunity?”

- Influence: “Can the organization realistically control or affect it?”

Issues that score high on all three deserve top priority.

For example, a software company facing high customer churn identifies multiple possible causes. Initial data links churn most strongly to poor onboarding rather than to pricing or competition. Applying the “focus on value” principle, the team directs its analysis toward onboarding experience metrics while monitoring the other causes. The result is faster insights and targeted recommendations.

Prioritization is a deliberate discipline. Selecting focus areas requires confidence. Leaving some issues unexplored is not oversimplification; it is strategic discipline. This approach also requires transparency with stakeholders regarding why certain areas are prioritized and others are not.

2.2 Evaluate Feasibility and Influence

High value is meaningless if an organization cannot act on it.

Feasibility refers to the extent to which an issue can be addressed within existing constraints, while influence refers to the ability to affect its outcome.

Many frameworks, such as the impact–influence matrix (see Section 3.1), explicitly balance these two dimensions. Issues with both high value and high feasibility are prioritized. Those with low feasibility may be flagged for long-term action or monitoring rather than immediate focus.

2.3 Sequence Based on Timing and Dependencies

Prioritization is also about knowing when to act. Some analyses or actions must be completed early because they are time-sensitive, unlock later work, or address urgent risks. Others can wait safely.

Dependencies matter. For example, a pricing analysis may be impossible before customer demand data is validated. Identifying the critical path early prevents wasted effort and keeps the project moving forward.

2.4 Align with Stakeholder Priorities

No matter how analytically sound your priorities are, they will fail without stakeholder support.

Stakeholder alignment means ensuring your focus areas align with the expectations, constraints, and incentives of key decision makers.

Aligning with stakeholders is essential for various reasons:

- Gaining buy-in: Priorities that reflect executive focus are more likely to get attention and resources

- Avoiding resistance: Analyses that ignore politically sensitive areas or push against stakeholder incentives can stall or backfire

- Communicating impact: Prioritized efforts that link clearly to stakeholder objectives are easier to explain and defend

Sometimes, stakeholder preferences conflict with analytical priorities. In such cases, strong problem solvers are needed who:

- Engage in early dialog to test receptiveness to specific solutions.

- Frame recommendations in stakeholder-relevant terms (e.g., “This addresses the board’s quarterly KPI”).

- Offer option sets: One aligned with stakeholder comfort and another that maximizes analytical value, with a clear explanation of trade-offs.

This creates a collaborative environment in which prioritization is viewed as a shared judgment rather than a rigid prescription. It does not mean abandoning analytical rigor. Rather, it means actively engaging stakeholders to identify blind spots, test assumptions, and find intersections between analytical value and organizational reality.

For instance, a hospital system may identify IT upgrades as the most promising way to reduce patient wait times, but if no budget is available, this option is not feasible. Instead, the team focuses first on redesigning triage and allocating staff—actions with both stakeholder support and immediate feasibility—while keeping IT improvements in a longer-term plan.

In short, prioritization lacking stakeholder alignment may be efficient, but not effective.

2.5 Stay Flexible and Reprioritize: Adaptability

Prioritization is not a one-time decision; it is an ongoing process. New data, changing conditions, and shifting stakeholder priorities can make the original plan outdated.

Adaptability is the ability to revise, reorder, or redirect focus based on emerging evidence or changing conditions.

It supports the ability to intelligently pivot based on:

- Analytical efficiency: Teams avoid spending weeks on lines of inquiry that later turn out to be irrelevant.

- Stakeholder engagement: Maintaining alignment and credibility requires being able to shift priorities in response to new directives.

- Solution quality: Teams increase the likelihood of solving the actual problem, not just the initially suspected one, by staying open to better insights.

Disciplined flexibility means changing course only when clear evidence or constraints justify it, rather than chasing every new idea. Regular checkpoints, such as progress reviews, stakeholder updates, and internal synthesis sessions, help keep priorities current without losing focus. This requires:

- Clarity of initial priorities so that changes can be compared against a baseline

- A lightweight documentation trail explaining why certain paths were paused or reactivated

- Team alignment to ensure that everyone understands what changed and why

For instance, a regional airline team may initially focus on fuel costs but later discover that declining occupancy rates are the main cause of margin pressure. They then pivot to pricing and scheduling, uncovering a more accurate diagnosis and stronger solution.

In short, adaptability does not negate focus. Rather, it preserves focus when conditions change and protects against overconfidence and tunnel vision.

3. Tools and Techniques for Prioritization

Prioritization decisions become sharper and more defensible when supported by structured tools and techniques. These provide teams with a shared language and framework for determining which issues to address first, thereby bringing rigor and transparency to what would otherwise be a subjective or politically charged process.

Prioritization tools are structured methods, visual frameworks, or simple models that help problem solvers evaluate importance, feasibility, timing, and impact so that resources can be allocated where they will be most valuable.

It is useful to distinguish between:

- Tools: Stand-alone lenses or filters used to evaluate options, such as matrices and estimation methods

- Processes: Sequences of actions that apply those tools over time

- Heuristics: Fast, experience-based rules of thumb (see Section 4)

Structured tools do not replace judgment; rather, they amplify it by clarifying trade-offs, grounding conversations in shared logic, and creating artifacts that can be revisited. In complex settings involving multiple stakeholders, competing hypotheses, uncertain outcomes, and pressure for both speed and accuracy, these tools offer clear advantages:

- Efficiency: Avoid analytical sprawl and focus effort where it counts.

- Consistency: Apply shared methods across teams.

- Transparency: Show stakeholders why certain issues are prioritized.

- Adaptability: Reposition priorities as new evidence emerges.

3.1 The Impact–Influence Matrix

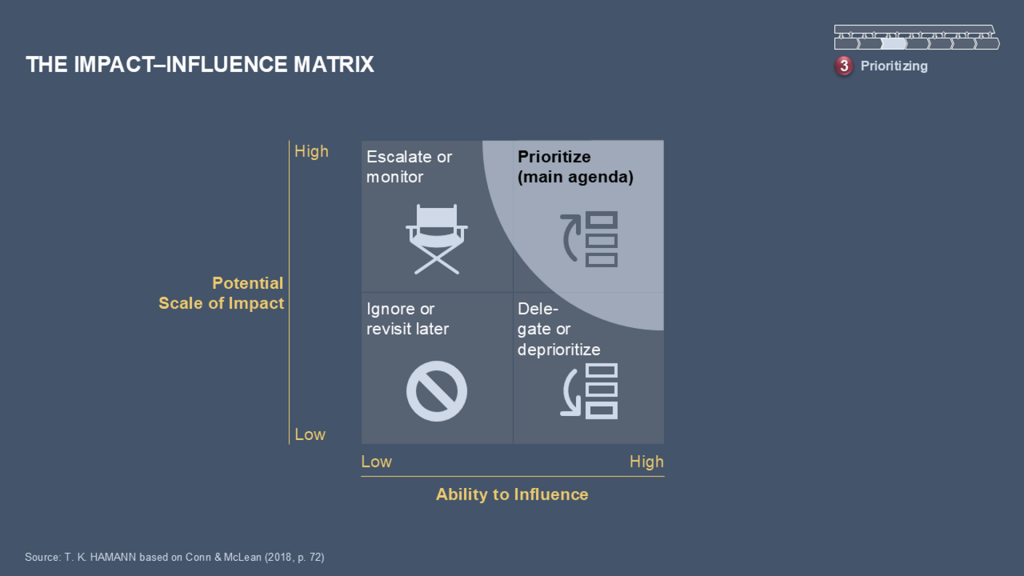

The impact–influence matrix is one of the most widely used prioritization frameworks. It evaluates each issue or hypothesis based on two criteria:

- Impact: “How significantly would resolving the issue advance the desired outcome?”

- Influence: “To what extent can the organization control or affect the issue?”

These dimensions are plotted in a two-by-two grid, creating four quadrants (see Exhibit 2).

This visualizes trade-offs and helps you avoid overinvesting in uncontrollable or low-value items. It is most effective immediately after structuring a logic tree and again mid-project when the agenda may need to change.

How to apply:

- Define your list of branches, hypotheses, cost drivers, or workstreams.

- Estimate the relative impact by combining it with other tools, such as back-of-the-envelope estimates (see Section 3.5) or quick heuristics like the 80/20 rule (see Section 4.1).

- Assess influence and feasibility by considering controllability, stakeholder buy-in, resources, and constraints.

- Plot and discuss: Use team dialogue to refine positioning.

- Prioritize by focusing on the high/high quadrant and deciding how to monitor or delegate the rest (see Exhibit 2).

For example, a manufacturing firm may identify six causes of production delays. Batch scheduling and machine downtime fall into the high/high category and become the focus. Supplier variability (high/low) is monitored, IT system limitations (low/high) are deferred, and quality control (low/low) is dropped.

Watchouts:

- Ratings are partly judgment-based—validate them with diverse input.

- Simplicity can hide nuance—reassess as data changes.

- Issues can move between quadrants over time.

3.2 Additional Filters: Time Sensitivity and Financial Relevance

While impact and influence are important, urgency and financial relevance often determine the outcome in real-world settings.

- Time sensitivity: “How soon must this be addressed to avoid missed opportunities, penalties, or delays?”

- Financial relevance: “How directly does it affect revenue, cost, margin, or key metrics?”

These filters ground prioritization in operational reality. Even a high-impact issue might be deferred if it is neither urgent nor financially significant. Conversely, a moderate-impact issue might rise in priority if delay is costly.

For example, a logistics company may face challenges in route optimization, driver scheduling, fleet maintenance, and warehouse management. Fleet maintenance and driver scheduling are prioritized because each day’s delay incurs costs and service penalties. Route optimization, though valuable, is sequenced later.

Maintain a balanced view and avoid bias toward short-term wins at the expense of long-term strategy. Blend urgency with strategic relevance.

3.3 Critical Path Analysis

Critical path analysis (CPA) adds timing and dependency considerations to the prioritization process. It identifies the sequence of tasks that determines the earliest possible completion of a project or analysis. Delays in these “critical” tasks delay the entire effort.

The critical path is the longest chain of dependent activities; any delay here extends the total timeline.

Why CPA Matters? CPA shifts the question from “What’s most important?” to “What must happen now for everything else to succeed?” This is particularly useful when deadlines are fixed, workstreams are interdependent, or certain insights unlock others. Specifically, it helps to:

- Prioritize sequencing: Know what must be done first. Avoid delays caused by bottlenecks or resource conflicts.

- Identify bottlenecks: Focus on the tasks that are holding you back. Identify the tasks that must start now, even if others can wait.

- Defer or parallelize: Flag items that can be done later or left for another time. Allocate limited capacity where timing matters most.

How to Apply:

- List all the key tasks or workstreams needed to solve the problem or implement the solution. Then, break down the problem-solving plan into its major activities, analyses, and deliverables.

- Identify and map dependencies: “Which tasks depend on the completion of others?” Determine which tasks depend on the completion of others. For instance, customer insights cannot be synthesized until the survey data is cleaned.

- Estimate Durations: Use rough time estimates to determine how long each task will take, even if only in hours or days.

- Identify and map the critical path: Trace the sequence of tasks from start to finish and identify the longest chain of dependent activities. These activities determine the minimum total time required for completion. This is your critical path.

- Prioritize and focus your attention accordingly: Tasks on the critical path should be prioritized because delays here affect the total timeline. Non-critical tasks can be delayed without affecting the overall delivery date. These tasks are said to have “float” or slack time.

A simple Post-it note exercise or MS Excel timeline is often sufficient. The goal is clarity about what needs attention now, not software-driven precision.

For example, in a board presentation, the financial model is on the critical path because the storyline depends on it. Competitor analysis is a stand-alone task and can be omitted if time is limited.

Watchouts:

- Do not confuse “time-consuming” with “critical.”

- Avoid overbuilding—this is a thinking aid, not bureaucracy.

- Revisit as conditions change.

3.4 Hypothesis-Driven Planning

Instead of exploring every branch equally, hypothesis-driven planning focuses analysis on the most critical assumptions about a problem’s causes or drivers.

Hypothesis-driven planning is a method that structures analysis around testing explicit, early hypotheses.

How to apply:

- Form working hypotheses early, e,g., “Churn is driven by onboarding delays.”

- Design the analysis to confirm or refute them quickly.

- Prioritize branches that, if disproven, would reshape the solution.

- Prune or replace hypotheses as evidence emerges.

For example, a renewal-rate project may start with the hypothesis that inactive product features cause non-renewal. Initial data supports this hypothesis, so the team deprioritizes pricing analysis and focuses on engagement.

3.5 Back-of-the-Envelope Estimation

Quick, logic-based approximations can help determine if an issue is significant enough to warrant a full analysis.

A back-of-the-envelope estimate is a rough calculation that uses simple assumptions to gauge the scale, value, or probability of an issue.

Why does it matter?

- It enables early prioritization when data is scarce.

- It prevents overinvesting in low-impact areas.

- It supports other tools by providing quick impact estimates.

Back-of-the-envelope thinking is especially valuable in the early or middle stages of a problem-solving effort, in dynamic environments where certainty is impossible and speed is essential, and when the team is trying to:

- Narrow down which options merit full analysis

- Validate whether a hypothesis is even plausible

- Quickly assess whether a branch of a logic tree has meaningful value

- Make interim decisions in data-poor environments

How to Apply:

- Break the problem down into measurable parts (volume × unit value).

- Use reasonable, rounded assumptions.

- Document your logic in case it is challenged.

- Ask: “Is it significant enough to justify further work?”

For example, improving the checkout page load time could increase conversions by 10 percent, generating an additional USD 75,000 in revenue per month. Even without perfect data, this result justifies further work.

Although there is no single formula, good estimates follow a few principles:

- Use round numbers: Focus on orders of magnitude (e.g., the difference between thousands and millions) rather than decimals.

- Work with known quantities: Begin with base rates, averages, or assumptions based on real-world experience.

- Document your assumptions: Make your logic transparent so that it can be challenged or improved.

- Check the outcome for sense: Ask yourself, “Does this result seem reasonable?” Use your business intuition to validate the number.

Always state the purpose of your estimate. You are not calculating exact profits—you are determining whether something is worth further investigation.

Remember, back-of-the-envelope estimates use assumptions and simple math to provide a rough sense of scale. The goal is speed and practicality, not perfect accuracy.

Watchouts:

- Do not stack too many weak assumptions.

- Make sure stakeholders understand that these results are only directional.

- Use them for triage, not as a substitute for detailed analysis when needed.

3.6 Combining Tools for Smart Pruning

No single tool fits every case. Strong teams combine them.

- Use the impact–influence matrix to determine an initial focus.

- Apply time and financial filters to make decisions.

- Use critical path analysis to sequence.

- Use hypothesis-driven planning and back-of-the-envelope estimation to test worthiness early on.

Together, these steps form a defensible process for pruning logic trees (see Section 5.6) and maintaining focus on what truly matters.

4. Heuristics for Fast and Smart Prioritization

In high-velocity or high-uncertainty environments, problem solvers often need to make decisions before having all the necessary data or time for a thorough analysis. Although structured tools provide rigor, they sometimes require inputs that are unavailable early on. In those moments, heuristics—experience-based rules of thumb—become accelerators.

A heuristic is a simple, experience-based shortcut that helps make sound decisions when time, data, or certainty is limited.

Heuristics complement, but do not replace, structured methods. They:

- Speed up the application of tools such as the impact-influence matrix or critical path analysis when inputs are incomplete.

- Turn early hypotheses into quick action filters.

- Help teams maintain momentum and focus while waiting for deeper analysis.

When applied consciously, heuristics act like the practical instincts of structured problem-solving: fast, selective, and grounded in business logic.

Heuristics are specifically effective when:

- A decision is needed immediately, but a full analysis is not feasible

- Data is incomplete or only directional

- Teams face multiple competing branches in a logic tree

- Stakeholder attention is short, and messaging must be concise

- Quick insight is needed to sequence deeper work

In such cases, heuristics serve as initial filters, not final verdicts: “Based on what we know now, here’s where to focus—then we’ll refine if needed.”

Heuristics matter in team settings because they create a shared language. Phrases such as “Let’s not boil the ocean” (see Section 4.2) and “Think in orders of magnitude” (see Section 4.3) quickly align people, signaling a shift in scope, speed, or depth.

However, they are not foolproof:

- When misapplied, they can reinforce bias or overlook important low-frequency risks.

- They work best as starting points—always be ready to adjust when new evidence appears.

4.1 The 80/20 Rule (Pareto Analysis)

The 80/20 rule, also known as Pareto analysis, is one of the most fundamental heuristics for solving problems and setting priorities. It acts as a filter: not all branches of a logic tree are equally important and the 80/20 rule helps us focus on the few factors that generate the greatest impact and hence deserve deeper attention. Typically, 80 percent of effects stem from 20 percent of causes.

When applied to problem solving:

- Identify the “vital few” drivers—often just two or three—that explain most performance gaps, costs, or risks.

- Use quick counts, directional data, or stakeholder feedback. Perfect precision is not required.

This approach cuts through long lists, accelerates early scoping, and frees resources for high-leverage work.

To apply the 80/20 rule:

- List all potential contributors to the problem, such as branches of a logic tree, drivers, and failure points.

- Quantify the impact, if possible. Examples could include indicators like the number of customer complaints per cause, the share of revenue by product or region, and the amount of downtime caused by equipment type.

- Rank items, issues, or subcategories by size, frequency, or financial impact. Sort them from highest to lowest visually, often using a Pareto chart.

- Identify the “vital few” top contributors, that are often a small subset responsible for most of the outcome. For instance, the top 20 percent of items often explain around 80 percent of the outcome.

For example, in a telecom call center study, two causes (agent availability and call routing errors) accounted for 60 percent of complaints. The team focused its analysis on these two causes and deferred the other six.

Best used with: the impact–influence matrix, back-of-the-envelope estimation, and logic tree pruning (see Section 5.6).

4.2 Do Not Boil the Ocean

Do not try to tackle everything at once. Although comprehensive analysis may feel safer, it dilutes focus, slows results, and exhausts teams.

“Boiling the ocean” refers to the futile attempt to tackle all parts of a problem simultaneously, rather than focusing on the few issues that matter most; it leads to analytical overload and delays in generating actionable insights.

To avoid this pitfall, teams must be deliberate about where and why they focus. This begins with applying the following checks early in the process.

- Revisit your framing: “What is the actual decision at hand?” Anything unrelated to that decision is noise.

- Refer to your logic tree: You do not need to analyze every branch.

- Use tools such as the impact–influence matrix to determine which issues warrant further analysis and back-of-the-envelope estimations to est assumptions quickly to determine if further analysis is necessary.

- Apply heuristics like the 80/20 rule: ask yourself which 20 percent of factors are likely to account for 80 percent of the outcome. Focus on those factors.

- Use Prune your analysis plan: Treat your initial work plan as a hypothesis, not a mandate. Be prepared to revise or eliminate low-value workstreams.

Teams can deliver sharper, faster results by proactively narrowing the scope and avoiding irrelevant rabbit holes.

For example, a cost-reduction project skipped analyzing all regions. A quick analysis showed that three regions accounted for 75% of the costs, so the team focused on those regions.

4.3 Think in Orders of Magnitude

In fast-paced problem-solving environments, precision can be tempting but misleading. Teams often get stuck trying to calculate the exact value of something when a rough estimate would suffice. When deciding whether to analyze something further, rough logic can often provide the answer. The heuristic “think in orders of magnitude” helps avoid this pitfall by encouraging problem solvers to first estimate the size, value, or impact before delving deeper or ruling items in or out based on scale.

Thinking in orders of magnitude means estimating the approximate size or scale of a variable rather than seeking exact numbers; this method enables faster prioritization and helps determine whether a topic is worth further analysis.

Therefore, estimate before analyzing in depth. Ask yourself: “Is this big enough to matter?”

- Use rough ranges (tens, hundreds, thousands) instead of chasing exact numbers.

- Support quick triage: low-value branches can be dropped early.

For example, an idle-time study of a delivery network identified a potential lever that could save USD 50,000 per year on a USD 200,000,000 cost base. However, the branch was deprioritized.

Best used with: Back-of-the-envelope estimation and “do not boil the ocean.”

4.4 Let Hypotheses Guide Prioritization

Without hypotheses, problem solving becomes a data-driven free-for-all. Teams may analyze everything, hoping that insights will magically emerge. This often leads to analysis paralysis, wasted time, and disconnected conclusions. Therefore, every analytical task should tie back to a hypothesis. If it does not, question its existence.

In contrast, leading with hypotheses helps teams:

- Focus initial efforts on high-value questions

- Sequence workstreams based on which ones need to be tested first

- Avoid aimless data collection and busywork

- Prune irrelevant analysis quickly to increase speed and clarity

Hypotheses do not eliminate creativity; they provide direction for it.

Follow these steps to implement hypothesis-driven prioritization into practice:

- Begin with your structure: Use logic trees or issue maps to identify potential causes of the problem.

- Form a hypothesis for each key branch: For example: “We believe that customer churn is primarily driven by product reliability issues.”

- Assess importance: “Would a proven hypothesis significantly change our recommendations?”

- Assess testability: “Can the hypothesis be quickly validated using existing data, interviews, or estimates?”

- Prioritize: Focus first on hypotheses that are both high-impact and testable. Delay or drop those that are speculative, low-value, or infeasible.

Hypotheses should be clear, falsifiable statements, not vague directions. A good test is: “Can we design a simple test or analysis to prove whether this is right or wrong?”

For example, a team is investigating the decline in online course completion rates. According to the logic tree, there are four possible causes: content quality, user interface design, learner motivation, and technical platform issues. Rather than analyzing all four equally, the team forms hypotheses:

- “Learners drop off due to lack of real-time feedback.” (content)

- “Users find the platform frustrating to navigate.” (interface)

- “Motivation drops when modules are too long.” (motivation)

- “Technical glitches interrupt access.” (platform)

They decided to test the interface hypothesis first using click-path data and session logs. If the hypothesis is true, resolving this issue could solve most of the problem. They will only allocate effort to the others if it is disproven.

Prioritization based on hypotheses is not without pitfalls:

- Confirmation bias: Teams may unconsciously favor data that supports their initial beliefs.

- Overconfidence: Rushing to conclusions before conducting thorough testing can result in faulty recommendations.

- Missed signals: Focusing too much on one branch can obscure emerging drivers elsewhere.

To mitigate these issues, teams should:

- Regularly revisit and revise their hypotheses.

- Encourage disconfirming evidence.

- Use tools such as back-of-the-envelope estimates and other heuristics like triangulation (see Section 4.7) to validate assumptions.

4.5 Apply the Elevator Test

In executive settings, attention is a scarce resource. Whether communicating with senior leaders, clients, or internal decision makers, conveying the importance of your work in simple, compelling terms is critical. The elevator test heuristic helps problem solvers determine whether their priorities and insights are clear and relevant.

The elevator test is a clarity check: Can you clearly and convincingly explain the value or relevance of a task, analysis, or insight in the time it takes to ride an elevator—roughly 30 seconds or less?

If you cannot, it may signal that:

- The analysis is not important enough.

- The thinking is not clear enough yet.

- The message is too complex or abstract for the intended audience.

The elevator test does not just test your ability to summarize. It tests strategic focus, communication clarity, and decision readiness. If you cannot explain why something matters in 30 seconds, reconsider it.

This heuristic is particularly useful before presentations or when challenged by a stakeholder. “Why are you working on this again?” Regularly apply the elevator test, especially at transition points in a project:

- Before launching a new workstream: “Can you explain why it matters?”

- Before providing stakeholder updates: “Can you explain the takeaway?”

- Before the final synthesis: “Can you summarize your findings concisely?”

- If a team member says, “We’re analyzing churn by age cohort,” ask, “What’s the implication? Why does that matter for the problem we’re solving?” If they cannot answer clearly, the analysis may need to be reframed or deprioritized.

Make the most of the elevator test:

- Start with the “So what?”: “What is the insight, rather than just the activity?”

- Be audience-aware: Use language that aligns with your stakeholders’ priorities.

- Avoid jargon: Use plain language to make your insights obvious.

- Link to business impact: Connect the message to financials, operations, or decision outcomes.

If your summary seems vague or too academic, refine your thinking. Often, clarity in communication reveals clarity in thought.

For example, “Sending fewer, targeted emails could cut churn by 8 percent and save USD 1,200,000 per year” is acceptable, while “We found a negative slope in our regression” is not.

4.6 Identify Key Drivers Early

This heuristic encourages problem solvers to first focus on the few high-leverage inputs or causes that disproportionately influence the problem at hand.

Drivers are the underlying causes, levers, or variables that most influence a problem’s outcome.

Identifying and analyzing them first accelerates progress and prevents wasted effort. Most outcomes are driven by a few core variables. The heuristic is simple: identify the most important levers early on. Use stakeholder interviews, benchmarking, or even gut checks to quickly identify these drivers.

This heuristic reflects a practical truth: to improve performance, you do not need to understand everything; you just need to understand the most important things first.

This supports the use of the 80/20 rule and makes the overall agenda more efficient.

Finding the true drivers requires more than guesswork. It requires a blend of analytical insight and business judgment. Some useful approaches include:

- Start with hypotheses: Ask yourself, “What could explain the performance gap or opportunity.” Then, test those hypotheses using structured thinking and light-touch analysis.

- Use historical data and trends: “Which variables demonstrate strong correlations, or even causality, over time?”

- Interview stakeholders: Internal teams and customers often know which levers matter most. Their insights can quickly refocus efforts.

- Build simple diagnostic models: Even a basic regression or index can identify the factors that most strongly correlate with the outcome.

- Rely on precedents: “What were the key drivers when similar problems were solved before?”

After identifying two to three primary drivers, you can base your entire analysis and recommendation on them. Focus your analysis there and defer peripheral causes.

For example, in a study of a sales decline, three factors—competitor bundling, reduced marketing spending, and brand perception—became the focus, replacing a long initial list.

4.7 Triangulate When Data Is Scarce

Many real-world problems do not come with clean data sets or perfectly measurable variables. In fast-paced or opaque environments especially, problem solvers often must make progress without having “all the numbers.” In such cases, triangulation comes into play as a critical heuristic.

Triangulation is the process of using multiple independent sources or perspectives to estimate or validate a result, especially when hard data is incomplete, conflicting, or unavailable.

Rather than waiting for perfect information, effective teams use different types of evidence—quantitative, qualitative, comparative, and anecdotal—to develop an accurate overall picture. It is about building confidence through convergence.

Combine multiple partial sources to gain directional clarity:

- Internal benchmarks: “How does this compare with other business units, time periods, or similar projects?”

- External comparables: “How do competitors or similar companies handle similar situations?”

- Expert interviews: “What do frontline managers, customers, and domain experts have to say about the issue?”

- Quick math: Use the rough Back-of-the-Envelope Estimates to determine the possible range.

- Qualitative patterns: Look for recurring themes in complaints, feedback, and field notes.

While none of these sources are decisive on their own, together they can provide a solid foundation for prioritization and decision making.

For example, a decision to close a sales office used productivity benchmarks, manager interviews, and cost-per-sale estimates to make a defensible recommendation despite lacking perfect data.

4.8 Look for Quick Wins/Low-Hanging Fruit

While prioritization often focuses on solving the most complex or high-impact elements of a problem, there is also significant strategic value in identifying and acting on quick wins—solutions that require minimal effort but deliver immediate, visible value. In fast-paced or politically sensitive environments, quick wins can build momentum, earn credibility, and create space for deeper analysis.

Quick wins are low-effort, high-payoff actions that can be implemented quickly, typically without extensive analysis or significant stakeholder negotiations; these actions are sometimes referred to as “low-hanging fruit” or “no-regret moves.”

Identify and implement low-effort, high-payoff actions early on:

- Look for pain points with obvious solutions: These are typically issues that stakeholders are aware of but have not addressed due to inertia, gaps in ownership, or competing priorities.

- Scan for gaps in policies, processes, or communications that can be addressed without major system or structural changes.

- Use back-of-the-envelope estimates to quickly validate value, ensuring the effort is low-cost and high-payoff.

- Use the impact–influence matrix: Target items that have a high influence score, even if their impact score is moderate.

Often, quick wins reside in operational details, such as improving internal handoffs, simplifying approval steps, clarifying roles, fixing visible customer pain points, and publishing clearer guidance.

4.9 Maintain a Big Picture Perspective

Strong prioritization means keeping the big picture in mind. Periodically zoom out to ensure that the analysis is solving the right problem and is aligned with strategic goals. Remind teams to take a step back and ask themselves, “Are we solving the right problem?” and “Are we focused on what the organization cares about?”

This perspective ensures the analytical agenda stays relevant and prevents over-investing in interesting yet irrelevant details. It also ensures the final story will resonate with decision makers.

4.10 Linking Heuristics to the Broader Toolkit

Heuristics sharpen prioritization by:

- Acting as quick filters before full tool application

- Keeping teams aligned and preventing scope drift

- Accelerating early phases, such as initial scoping, mid-course adjustments, and pre-synthesis

When linked to the structured tools in Section 3, heuristics strike a balance between speed and structure, intuition and discipline, making prioritization faster and smarter.

5. Prioritization in Action: When and How to Prioritize

Prioritization is not a one-time event at the beginning of a project. Rather, it is a dynamic, iterative discipline that guides problem solvers at critical junctures, shaping focus, adjusting effort, and aligning resources with the greatest potential for impact

While understanding the principles, tools, and heuristics of prioritization is essential, knowing when and how to apply them in practice turns a well-structured plan into tangible results. Prioritization adds the most value when woven throughout the process, from framing to synthesis, rather than being treated as an early checklist item.

It is the continuous process of evaluating and organizing efforts according to importance, feasibility, and timing. It ensures that scarce attention, time, and energy are directed toward the most valuable and actionable tasks.

This Section outlines three pivotal moments in problem solving when prioritization decisions matter most and explains how to effectively apply earlier tools and heuristics. The goal is to treat prioritization as an active mindset, applied early, revisited often, and adjusted with confidence, rather than as a static decision.

The most effective problem solvers are not those who analyze the most but rather those who focus where it matters most—early, often, and with conviction. They:

- Start strong: Prioritize immediately after structuring to cut through the noise and choose the highest-value areas for deeper work.

- Stay adaptable: Reprioritize midstream when new evidence emerges and shedding low-impact areas while doubling down on hidden drivers.

- Finish sharp: Shift from analytical breadth to communicative clarity in the final stretch to ensure the final recommendation is crisp, relevant, and decision-ready.

Even the best prioritization logic fails without execution. High-performing teams operationalize it, translating focus into task ownership, sequencing, resource allocation, and visible workflows. They make prioritization a weekly habit, documenting decisions transparently and aligning their focus with evolving goals. They avoid common traps such as overanalyzing, clinging to outdated plans, and chasing stakeholder noise.

Ultimately, prioritization transforms structure into strategy and effort into impact.

5.1 A Dynamic Process

Effective prioritization is flexible. It evolves as new insights surface, circumstances shift, and constraints change. In the early phases, priorities are often guided by directional hypotheses. Later, they are refined by evidence, emerging risks, and stakeholder input.

Dynamic prioritization involves deliberately refining and reordering focus areas throughout the process in response to evolving data, context, and feasibility.

A static plan quickly becomes irrelevant. Teams that adhere rigidly to initial priorities may miss breakthroughs, overlook emerging threats, or waste time on low-value work due to habit or sunk-cost bias. In real-world projects, many valuable discoveries occur midstream, not on day one.

Make prioritization adaptive by:

- Scheduling reevaluation moments: Build checkpoints, such as midpoint reviews, pre-synthesis huddles, and stakeholder updates, to confirm that the focus remains appropriate.

- Watching for change signals: Disconfirming evidence, shifts in market context, or reframing by stakeholders.

- Maintaining a “Not Now” list: Park deprioritized items that might merit attention later if conditions change.

- Documenting your rationale: Explain priority changes to maintain trust and alignment

For instance, a team studying employee disengagement initially focuses on compensation and career paths. Midway through, interviews reveal that managerial behavior and team culture are far more important drivers. The team trims the original scope and doubles down on leadership effectiveness, resulting in sharper, more actionable recommendations.

5.2 Initial Prioritization: Right After Structuring

After structuring a problem into a logic tree or issue map, it can be tempting to explore every branch equally. Initial prioritization prevents this by directing efforts toward the most promising or riskiest areas first.

It bridges the structured framework and the first wave of analysis, ensuring that resources go where they can create early momentum and insight.

How should you prioritize after structuring?

- Assess for relevance: “Is this issue directly related to the central question or decision at hand?”

- Estimate impact and feasibility: Use tools such as the impact–influence matrix and heuristics like 80/20 thinking to determine which branches could produce meaningful results.

- Apply working hypotheses: Use the hypotheses created during the framing process to determine which branches are most likely to validate or refute them.

- Engage stakeholders for input: Early discussions with sponsors or internal experts can help you test your assumptions and identify politically sensitive areas that are worth addressing—or avoiding.

For example, a manufacturing revenue growth team identifies five potential drivers. Early data plus stakeholder input reveal that weak sales coverage in key regions is the main driver. Therefore, they focus on products and salesforce effectiveness and put geographic expansion and pricing on hold.

5.3 Mid-Process Reevaluation: Reassess Midstream Based on New Insight

Even strong initial prioritization can veer off course. As data accumulates and context changes, some priorities may become irrelevant, and new ones may emerge. Mid-process reevaluation protects against analytical inertia and ensures that resources remain aligned with what truly matters.

Follow these steps to reevaluate midstream:

- Review progress against hypotheses: “Which ideas have been validated, refuted, or left unresolved?” This will help you confirm that you are learning the right things.

- Compare new findings against your logic tree: “Are there any areas that seem irrelevant now, or that warrant more attention?”

- Reapply prioritization tools: Replot your issues on the impact–influence matrix or revisit the 80/20 filters to see if new insights change the ranking of your focus areas.

- Reengage stakeholders: Take this opportunity to test your initial conclusions, ensure alignment, and adjust your approach if new constraints or preferences have emerged.

These discussions are best framed as checkpoint meetings or interim synthesis sessions. This allows for tactical adjustments and strategic realignment.

For example, a subscription service team may start with pricing, product features, and customer service. Early surveys show that pricing is fine, but later data points to a problem introduced in a recent app redesign. The team then pivots, focusing on user experience (UX) while maintaining service analysis but dropping pricing from the active agenda.

5.4 Pre-Synthesis Prioritization

As the project moves toward synthesis, the focus shifts from analysis to presentation. Now is the time to distill, removing distractions, sharpening the storyline, and aligning with the needs of decision makers.

Prioritization before synthesis filters and frames insights so the final output is targeted, relevant, and ready for action.

How should you prioritize before synthesis?

- Revisit the original framing: Ask, “What was the core problem or question?” and “What decisions need to be made?” Each slide, insight, and recommendation should relate back to these questions.

- Sort insights by relevance and impact: Not everything learned deserves equal airtime. Use the impact–influence matrix or the 80/20 rule to identify the most significant insights.

- Refine the storyline: Use a top-down structure, such as Situation–Complication–Resolution (SCR) or Situation–Complication–Question–Answer (SCQA), to define the narrative. Any insights that do not support the storyline should be trimmed or moved to an appendix.

- Validate feasibility: Identify any recommendations lacking organizational buy-in or operational feasibility. These recommendations may need to be reframed, reordered, or replaced.

- Test with stakeholders: Share a draft of the storyline or a preview with sponsors and key decision makers. Use their feedback to refine the focus further and avoid late-stage surprises.

This process transforms a sprawling set of findings into a cohesive and compelling argument.

For example, a regional bank project yields multiple findings. The leadership team wants short-term margin improvement, so the project team focuses on pricing and cost levers, moves talent discussions to Phase II, and removes the macroeconomic context from the main story.

5.5 Embedding Prioritization into Daily Work

Prioritization only works if it is practiced daily. Teams should make it visible, deliberate, and repeatable.

Get used to these daily habits:

- Anchor your work in hypotheses: Use your initial assumptions to guide the agenda and validate or adjust them with data along the way.

- Design every workstream with value in mind: Ask yourself, “What decision does this help us make?” and “What is the likely impact if this is true?”

- Start with rough estimates: Before conducting a deep analysis, use back-of-the-envelope math to determine if something is worth the effort.

- Sequence tasks logically: Use critical path analysis to ensure that time-sensitive items are completed first and that no downstream activity is delayed unnecessarily.

- Reassess weekly: Schedule regular checkpoints for your project team (e.g., weekly reviews) to reevaluate priorities, adjust the scope of the project, and allocate resources based on the findings.

- Document what gets deferred: When pruning a logic tree or sidelining a topic, note why and under what conditions it should be revisited.

For example, a retailer’s supply chain project uses weekly priority reviews to eliminate irrelevant analyses (e.g., return rates) and accelerate deep dives into key bottlenecks. This keeps the team aligned and lean.

Even experienced problem solvers can fall into traps. Avoid these common pitfalls:

- Conflating urgency with importance: Just because something has a deadline does not mean it should be a top priority. Always link to impact and ask, “To what end?”

- Overanalyzing low-impact areas: Intellectual curiosity is valuable, but only if it helps find solutions. Curiosity must serve the objective. Use value screens regularly.

- Sticking with the original plan too long: Projects evolve. Prioritization should, too. So, Revisit priorities regularly and be willing to change course as you learn.

The antidote to these pitfalls is a culture of disciplined reflection—checking, often, whether you are still spending time on what matters most.

5.6 Pruning Logic Trees

A well-structured logic tree is a decision-making tool, not a to-do list.

Pruning involves removing or suspending low-value branches so that effort is concentrated on high-impact areas.

Here is how to prune:

- Test each branch for impact, influence, and relevance: Ask, “Does this branch present a significant opportunity or risk?” “Can the organization meaningfully influence it?” “Is it central to the working hypotheses or storyline?” “Will analyzing it help us make a better decision or recommendation?”

- Use tools and heuristics such as the impact–influence matrix, the 80/20 rule, quick sizing, and working hypotheses.

- Document what was pruned, why it was pruned, and under what conditions it might be reactivated.

For example, a retail performance study would drop pricing and marketing analysis early on if evidence pointed to store experience and location as the key drivers, freeing resources for deeper work where it matters.

6. Key Takeaways

Prioritization is not an ancillary activity; it is the driving force that transforms structured problem-solving into measurable impact. When done well, it allocates resources toward the most valuable opportunities. When done poorly—or not at all—it results in analysis overload, wasted effort, and diluted recommendations.

6.1 Why It Matters

- Resources are limited: Time, attention, data access, stakeholder patience, and analytical bandwidth are all finite. Without prioritization, even the most well-structured problem can become slow, costly, and unfocused.

- Prioritization transforms structure into focus: After mapping a full logic tree or hypothesis set, it determines which branches or hypotheses warrant deeper investigation. Prioritization is the mechanism that converts comprehensive structure into strategic discipline.

6.2 How to Do It Well

- Make it dynamic: Apply initial prioritization immediately after structuring. Then, conduct mid-process reevaluation and pre-synthesis prioritization as evidence emerges and contexts shift. Flexibility is responsiveness, not indecision.

- Follow clear principles: Focus on high-impact, high-influence areas. Apply the 80/20 rule, respect time sensitivity and critical path dependencies, and align with stakeholder priorities.

- Prune deliberately: Use pruning logic trees to remove or defer low-value branches and concentrate your efforts. Make pruning decisions based on evidence, document them, and ensure they are reversible.

6.3 With What Tools?

- Use the prioritization toolkit: The impact–influence matrix, critical path analysis, hypothesis-driven planning, and back-of-the-envelope estimates make prioritization concrete and actionable.

- Leverage heuristics: Rules such as “avoid ‘boiling the ocean,’” “identify key drivers early,” and “look for quick wins” help teams stay efficient under uncertainty or time pressure.

6.4 Avoid What?

- Common pitfalls: Confusing urgency with importance, clinging to outdated priorities, overanalyzing low-impact areas, and chasing stakeholder noise.

- Superficial execution: Prioritization must be operationalized through work plans, task sequencing, resource allocation, and visible workflows—not just captured in slides.

6.5 The Leadership Dimension

Prioritization is a leadership act. It reflects judgment, courage, and clarity—the willingness to say no to good ideas to make room for great ones. By embedding prioritization in execution, documenting decisions, and thoughtfully revisiting them, problem solvers protect their time, magnify their impact, and transform ambition into achievement.

References

Conn C, McLean R (2018) Bulletproof Problem Solving (Wiley, Hoboken, NJ).