The Iterative Eight Steps for Solving Problems – Step 7: Communicating

1. From Problem Solving to Selling the Solution

Problem solving does not reach its decisive moment when the analysis is completed, but rather when the solution is convincingly communicated and accepted by those empowered to act. No matter how methodologically sound or intellectually elegant the analysis is, it remains inert unless it moves people to make decisions and take action. Therefore, communication is not a peripheral skill; it is the critical bridge between insight and impact.

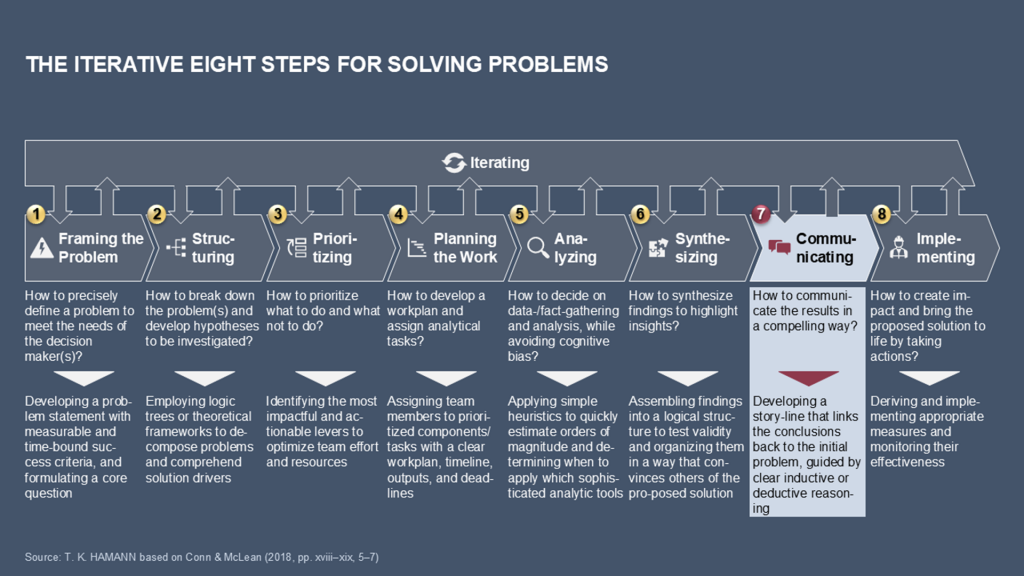

This is why communicating constitutes the seventh step of the Iterative Eight Steps for solving problems (see Exhibit 1). By this point, the problem solver has defined the challenge (framing the problem), broken it down into manageable parts (structuring), chosen the most important aspects (prioritizing), organized the workflow (planning the work), conducted rigorous analyses (analyzing), and combined findings into meaningful insights (synthesizing). At this stage, it is crucial to ensure that the results of this intellectual labor reach and resonate with the audience for whom the work matters most—the decision-maker.

In professional problem solving, communication is more than just the transmission of information. Rather, it is the strategic act of persuasion, helping others see, understand, and ultimately believe and act as you recommend. As Barbara Minto (2009), a former McKinsey & Company consultant, emphasized, communication is not about telling people what you did; it is about showing them what they need to think and do next.

2. The Purpose of Communication

The goal of the communication phase is to translate analysis into action by facilitating clear and confident decision making. Whether a client, executive, or board member, the decision-maker must be able to quickly grasp your recommendation, understand its rationale, and be motivated to act on it.

According to Minto (1996), decision-makers do not need to know everything the team did; they need to understand the implications and the next steps. This captures the essence of professional communication. It is not a diary of activity but rather a carefully constructed argument that leads the audience toward an actionable conclusion.

This requires shifting from a problem-solving mindset of “How can we figure this out?” to a solution-selling mindset of “How can we help others accept and implement this solution?” The focus shifts from intellectual exploration to narrative persuasion, resulting in three major outcomes:

- Clarity: the recommendation must be clear and unambiguous.

- Logic: the reasoning behind it must be transparent and defensible.

- Resonance: the audience feels that the solution fits their context, values, and needs.

When these conditions are met, communication becomes an act of leadership rather than reporting—a process of guiding others from understanding to commitment.

Based on this, effective communication addresses three fundamental questions.

- “What do we recommend?” — This is the core message or governing thought.

- “Why do we recommend it?” — The key supporting arguments or main idea.

- “How will it work?” — Supporting facts, analyses, and implications.

These three layers form the essence of structured communication. In practice, most unsuccessful presentations fail not because they lack facts, but because they obscure the governing thought, burying it under a mountain of detail.

The governing thought, also known as the core message, is a concise statement expressing your recommendation or answer to the decision-maker’s question; it encapsulates the significance of your analysis and establishes the direction of the subsequent narrative.

A compelling governing thought does more than summarize; it provides orientation. It signals clarity of purpose and confidence in one’s conclusions. When articulated at the outset, it helps your audience navigate the ensuing argument and reminds you, the communicator, of what truly matters.

3. From Synthesis to Storyline

Once the synthesis is complete, you will have a collection of findings, patterns, and insights that, when considered together, provide an answer to the problem. However, knowledge alone is not persuasive. The communicator’s challenge is to assemble these insights into a coherent storyline—a logical and emotionally resonant narrative that connects the dots from the original question to the recommended action.

The process begins with a revisit of the problem statement worksheet created during the framing and planning stages, as well as a reflection on alignment. Reexamining the initial scope ensures that communication remains anchored in the original intent of the client or sponsor. Ask:

- “What problem did we originally set out to solve?”

- “What were the success criteria or decision parameters?”

- “How has our understanding evolved during the analysis?”

- “Does our solution remain within the boundaries set by the decision-maker, or are we proposing to stretch them for valid reasons?”

Linking back to these questions explicitly demonstrates intellectual discipline and respect for the decision-maker’s framing of the issue. When your storyline mirrors the evolution of understanding of the problem, it signals that your solution is analytically sound and contextually grounded.

Such reflection also guards against the classic “answer in search of a question.” It reconnects the final message to the reality of the stakeholders, demonstrating intellectual discipline and empathy.

A well-crafted storyline conveys narrative tension and resolution. It mirrors the cognitive journey from uncertainty to clarity, inviting the audience to accompany the problem solver on that path.

4. Structuring the Story: The Pyramid Principle

The Pyramid Principle, developed by Barbara Minto (2009), is one of the most effective tools for structuring complex communication. It is now the standard method taught in consulting firms and business schools for presenting problem-solving outcomes.

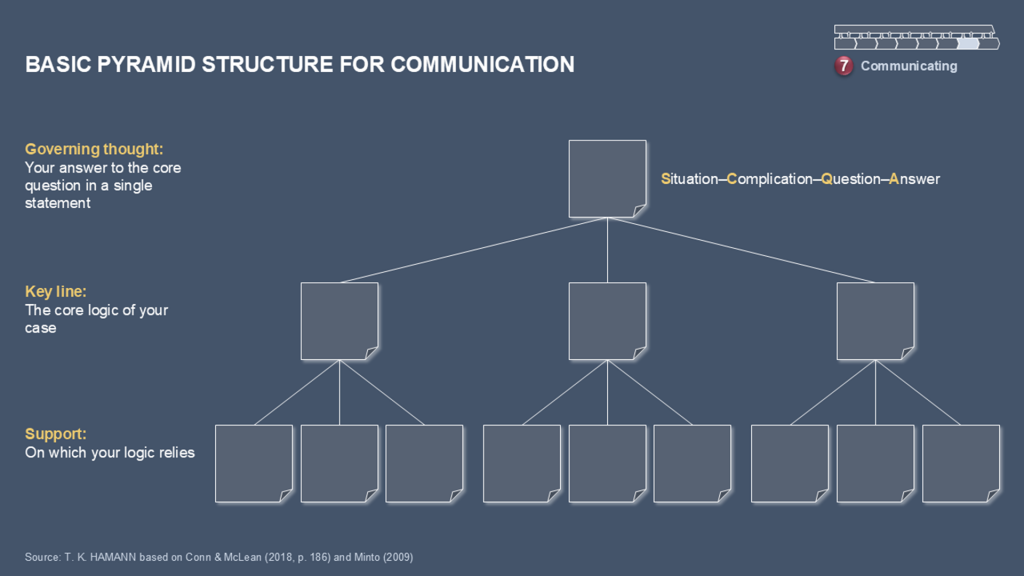

At its core, the Pyramid Principle is based on the simple yet powerful psychological concept that audiences understand ideas more easily when they are presented in a clear hierarchy—from the answer at the top, to the main arguments in the middle, and finally, to the supporting evidence at the base. The pyramid ensures that the logic of the argument is explicit and that every element supports the element above it.

The key line forms the middle layer of the pyramid. It comprises the main reasons or lines of logic that justify the governing thought. Each key-line argument must answer either a “why” or a “how” question raised by the governing thought.

As Exhibit 2 shows, the Pyramid Principle structures communication hierarchically. Each layer provides a logical foundation for the layer above it, which ensures that the audience can easily follow the reasoning from evidence to conclusion.

Exhibit 2 illustrates the logic hierarchy at the heart of the Pyramid Principle. The governing thought, the concise statement that captures your main recommendation or conclusion, sits at the apex of the pyramid. It is the “So what?” of your problem-solving effort and the answer to the decision-maker’s central question. Below that is the key line, which provides the main reasons or arguments that justify or explain that conclusion. These arguments should be mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive to ensure they cover the issue completely without overlapping. The base of the pyramid contains the supporting evidence: detailed data, analyses, and observations that substantiate each argument in the key line.

For example, imagine you are advising a company that wants to become profitable again. One possible recommendation would be to expand into a specific customer segment. The key line would present the most compelling reasons for this recommendation. It might state that the segment is growing faster than the market, that the company’s capabilities align with the segment’s needs, and that financial modeling shows attractive returns. Supporting evidence would include analytical materials substantiating these claims, such as market data, consumer research, financial projections, and competitor benchmarks.

Thus, Exhibit 2 reminds communicators that every effective message moves from answer to reason to proof. By organizing ideas in this hierarchy, communicators can guide their audience through a logical pathway from insight to conviction. This ensures that every piece of analysis directly supports the central recommendation.

In practice, building a pyramid means flipping your analytical tree on its side. What was a hypothesis tree during problem solving becomes a communication pyramid during storytelling. The governing thought (“We should invest in the premium segment to regain profitability”) sits at the top. Below that are the two or three most compelling arguments justifying this recommendation: “Because the segment is growing fast,” “Because our brand fits its needs,” and “Because financial modeling shows it is profitable.” Under each argument are the detailed analyses that support it.

This structure enables your audience to grasp the logic and evidence immediately. It also enables you to convey complex reasoning in a memorable and persuasive way.

5. Logic and Flow: Deductive and Inductive Reasoning

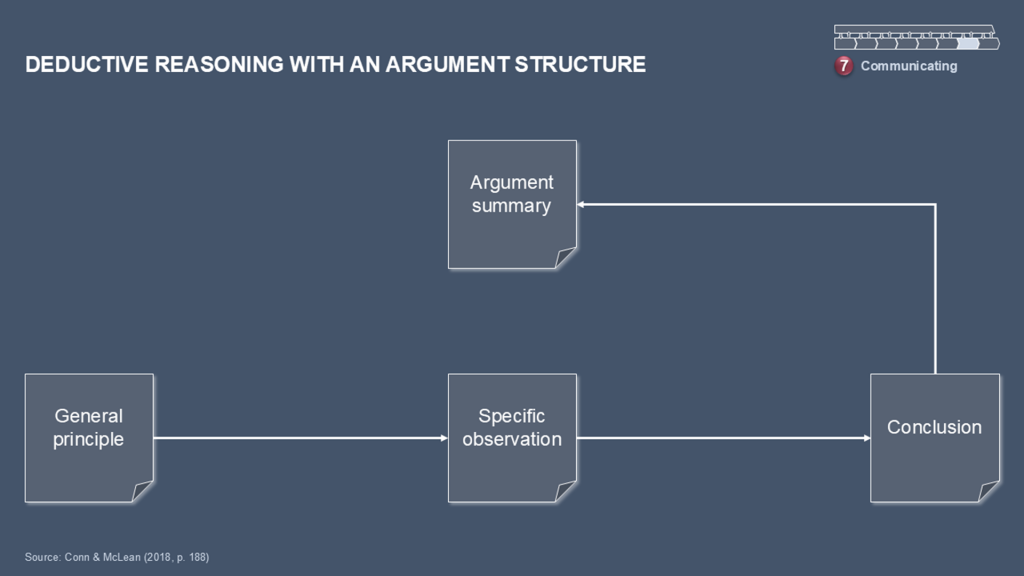

Every strong pyramid is based on clear reasoning. Two fundamental modes of reasoning shape persuasive communication: deductive and inductive logic.

Deductive reasoning starts with general principles and arrives at specific conclusions. It starts with a rule or hypothesis and applies it to specific situations. For example:

“If cost leadership drives competitiveness in our industry and our unit costs are the highest, then we must reduce costs to regain competitiveness.”

This is a linear chain in which each statement logically follows the previous one. This appeals to analytical audiences who value rigor and causality.

Exhibit 3 illustrates deductive reasoning as a logical cascade. A general principle (the major premise) leads to a specific observation (the minor premise), and the two together yield a conclusion. In communication, this structure supports messages requiring clear causality, such as policy recommendations or process changes. The strength of a deductive argument hinges on the validity of its premises and the precision of its wording.

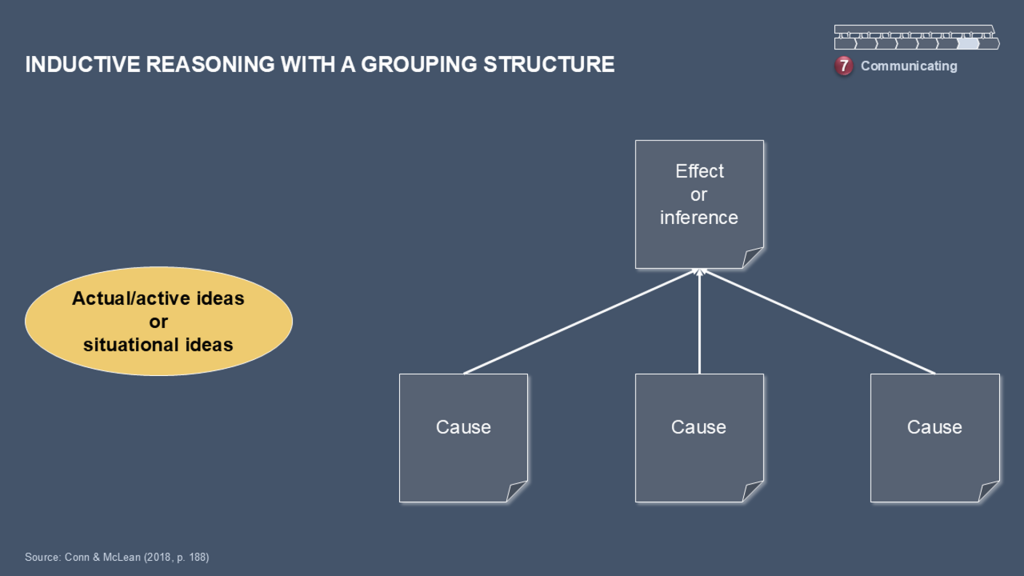

Inductive reasoning, in contrast, builds from specific observations toward a general conclusion. For example:

“Our last three product lines that adopted digital tools outperformed the others. Therefore, digital adoption appears to be a key performance driver.“

Induction feels natural and intuitive because it builds belief through accumulated evidence.

Exhibit 4 depicts inductive reasoning, in which several discrete observations or data points are combined to support a broader insight. This pattern is well-suited to findings based on patterns or trends, such as market analyses or summaries of customer research. The reasoning becomes more persuasive as the number, relevance, and consistency of observations increase.

Effective communicators blend both approaches: they use induction to establish credibility through facts and deduction to organize those facts into a coherent narrative.

The Situation-Complication-Question-Answer (SCQA) model translates reasoning into narrative form. It begins with a description of the current context (situation), introduces a tension or challenge (complication), poses the decision-maker’s core question, and provides a recommended answer.

Using the SCQA structure helps presenters organize complex material into a story rather than a report. The model creates a natural rhythm that mirrors how human cognition works: first, provide context; second, create tension; and third, offer a resolution. When executed effectively, the SCQA model engages both the intellect and the emotions, which is crucial in executive communication.

6. Designing the Storyline: The Discipline of MECE

The storyline is the backbone of your communication. It translates your pyramid logic into a sequence of points, arguments, and evidence. Before creating slides or visuals, you should have a textual storyline—ideally a concise, one-page outline.

A good storyline satisfies three criteria: logical completeness, non-overlap, and simplicity. These criteria are embodied in the MECE principle: mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive.

The MECE principle ensures that each element of your argument is distinct and that, collectively, they cover the entire scope of the problem. This principle prevents gaps and redundancies, ensuring clarity and focus.

Applying MECE requires discipline. When constructing your storyline, ask yourself:

- “Do my arguments overlap?”

- “Do they collectively address all relevant aspects of the problem?”

- “Can your audience easily follow the logic without confusion?”

Working in a MECE fashion organizes thoughts and reassures sophisticated audiences, such as senior executives, that the communicator has thoroughly explored the issue, resulting in precise and comprehensive thinking. This approach also simplifies the listening process. Audiences can trust that each argument adds a new piece to the puzzle rather than repeating what has already been said.

7. Storyline Patterns: Grouping and Argument

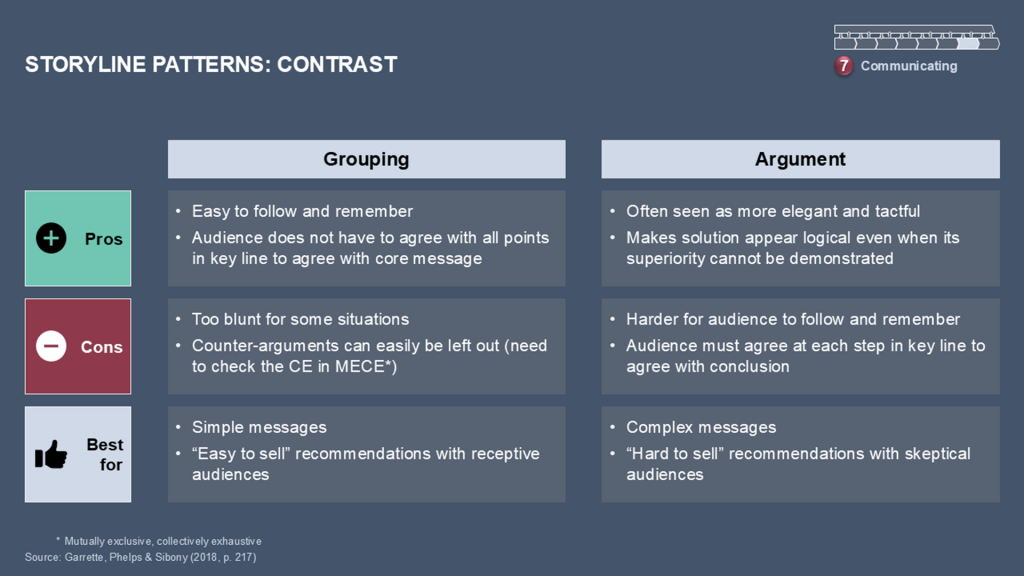

Once you understand the structure of the pyramid, you must decide on the reasoning pattern that best fits your audience and purpose. Not all storylines follow the same rhythm. Depending on the complexity of the issue and how skeptical the audience is expected to be, communicators can choose between two fundamental patterns of reasoning: grouping and argument. They can also combine elements of both.

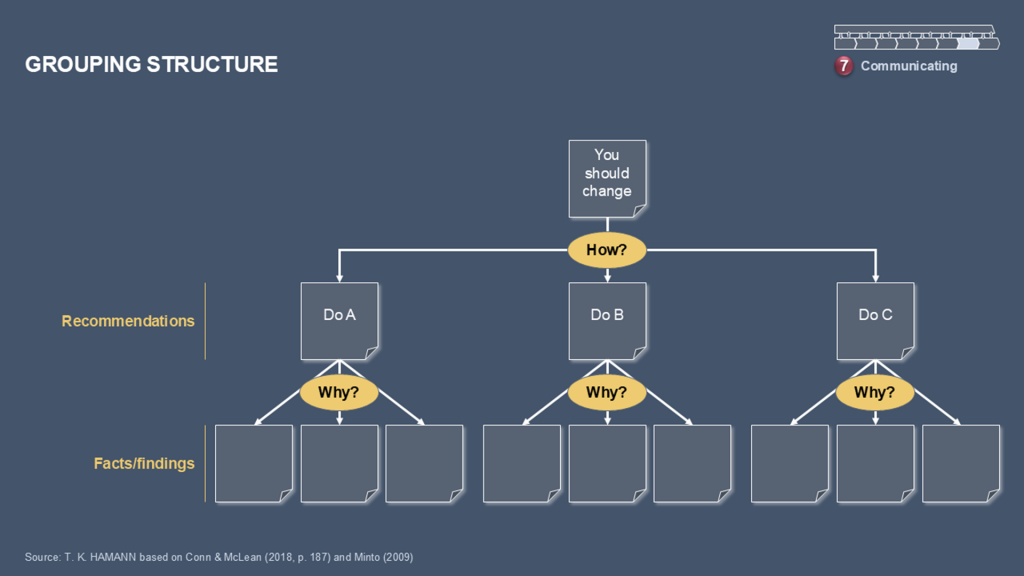

A grouping pattern brings together multiple independent reasons that support the same conclusion. This pattern is ideal when your audience is broadly aligned or when your recommendation is relatively uncontroversial. Exhibit 5 visualizes the grouping structure, in which multiple supporting arguments converge directly on the governing thought. For example:

“We should expand into market X because (1) demand is strong, (2) our brand is credible there, and (3) the economics are favorable.”

Each branch could stand alone as a justification. The advantage of this pattern is its robustness; if one argument is questioned, the others still hold. However, this pattern can appear abrupt to skeptical audiences because it asserts rather than persuades.

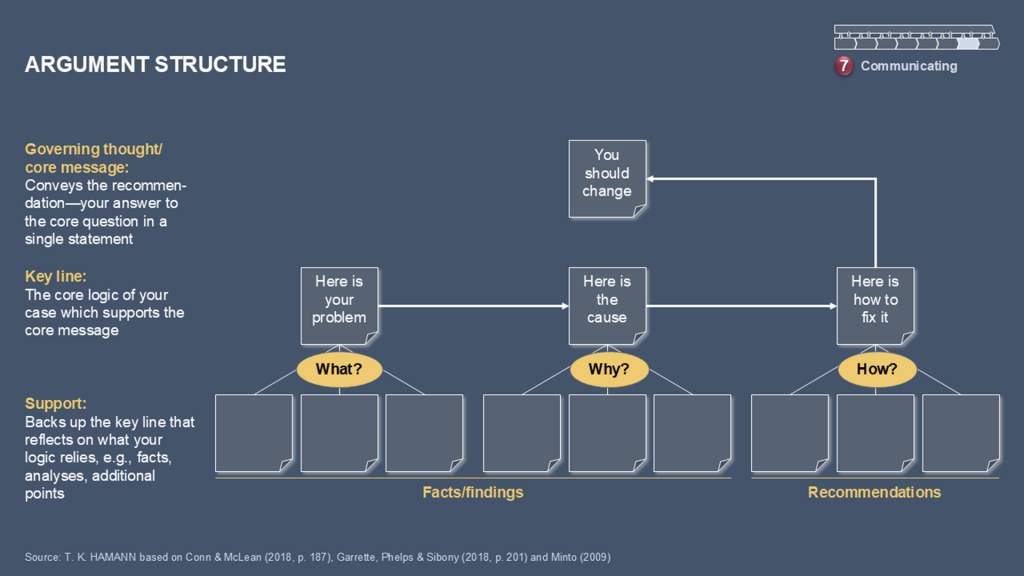

By contrast, an argument pattern unfolds sequentially, with each point building upon the previous one to reach the conclusion. This pattern is better suited to complex, ambiguous, or potentially controversial recommendations. Exhibit 6 portrays an argument pattern in which each idea builds upon the previous one. It might unfold as follows:

“The market is stagnating (situation); traditional strategies no longer deliver returns (complication); therefore, we must diversify into market X (answer).”

As previously mentioned, the groupings are clear and robust, though they can sound blunt. Arguments, on the other hand, are tactful and elegant but fragile. If one link fails, the chain breaks. Skilled communicators know when to use which pattern. They may even blend both patterns within the same presentation, combining the emotional tact of arguments with the analytical clarity of groupings. They often start with an argument to spark curiosity and conclude with a grouping pattern to reinforce belief. The ability to shift between these patterns marks the transition from competent to masterful communication.

Exhibit 7 contrasts the two structures. Grouping patterns are additive; they provide additional reasons to strengthen conviction. In contrast, argument patterns are progressive; they guide the audience through a process of reasoning.

8. From Storyline to Presentation

A well-conceived storyline must then be expressed in a tangible form, such as a slide deck or written report. Regardless of the medium, the underlying logic should be consistent.

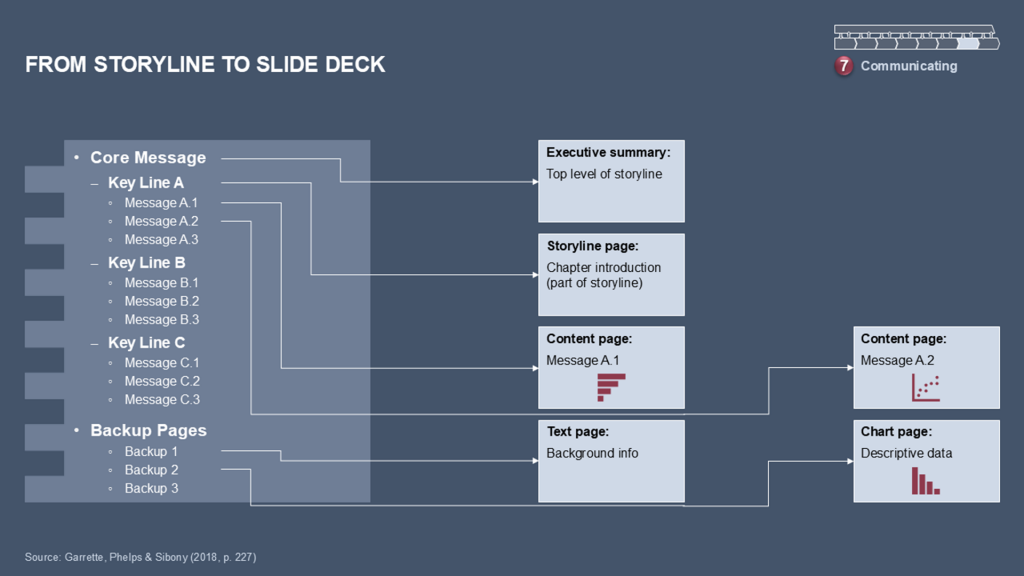

A professional communication package often includes the following:

- Executive summary: A one-page summary of your pyramid stating the main idea and key arguments.

- Storyline sections: Each section elaborates on one argument from the key line.

- Content pages: Each page or slide conveys one clear message expressed in an action title.

- Backup pages: These pages contain detailed data or appendices for reference, not for presentation.

Translating a well-structured storyline into a professional slide deck requires maintaining the integrity of the underlying logic while adapting it to a visual medium. The transition from a written argument to a presentation should not distort the message. Rather, it should make the reasoning more accessible to the audience. Exhibit 8 illustrates this translation process, showing how the storyline’s conceptual structure becomes the backbone of a clear and persuasive presentation.

Exhibit 8 shows how a carefully crafted storyline evolves into a coherent slide deck. The governing thought and key line forming the top layers of the communication pyramid are reflected in the executive summary and section headers of the presentation. Then, each argument from the key line is expanded into a sequence of content pages, each of which conveys one clear message supported by evidence in the form of charts, visuals, or key data points. The backup pages that follow provide analytical depth for reference, ensuring transparency and credibility without overwhelming the audience during the presentation.

This tiered structure enables the presentation to unfold logically and intuitively, guiding the audience from the overarching conclusion to the supporting evidence. It ensures that the storyline’s logical integrity remains intact while the slide format brings focus and visual clarity. Thus, the slide deck becomes a disciplined expression of structured thinking—a visual narrative that faithfully conveys the story’s reasoning and message, rather than a mere collection of visuals.

Each page should be self-contained yet connected to the overall storyline. When read aloud, the action titles should logically reconstruct your storyline. If they do not, your structure needs improvement.

Charts and visuals should illuminate the argument, not merely decorate it. Always ask yourself, “Does this visual help the audience understand the message?” If not, simplify or remove it.

9. Managing the Communication Process: Pre-Wiring and Tailoring

Effective communication does not begin at the final meeting. Effective communicators manage their message throughout the problem-solving process. Two complementary practices make this possible: pre-wiring and tailoring.

9.1 Pre-Wiring

Pre-wiring is the process of preparing key stakeholders for the final message. It involves sharing interim insights, testing reactions, and addressing objections in advance. This transforms the final presentation from a “big reveal” into a moment of confirmation and commitment.

Pre-wiring ensures that nothing in the final meeting will come as a shock. This is especially important when your recommendation challenges entrenched interests or assumptions. Engaging in one-on-one conversations, sending preview materials, and scheduling informal check-ins builds familiarity, reduces resistance, and encourages co-ownership of the outcome.

Pre-wiring serves three purposes:

- It reduces resistance; decision-makers rarely accept recommendations that catch them off guard.

- It improves quality by surfacing blind spots and helping to refine the story through early feedback.

- It fosters a sense of ownership: when stakeholders recognize their concerns and language in the final message, they feel invested in its success.

Pre-wiring does not mean leaking unfinished conclusions. Rather, it means engaging stakeholders through dialog by previewing hypotheses, asking for reactions, and adjusting emphasis accordingly. This continuous alignment ensures that, by the time the final presentation arrives, stakeholders are ready to endorse the recommendation.

9.2 Tailoring

Complementing pre-wiring is the art of tailoring—the ability to adapt your communication style to different audiences’ needs, preferences, and expectations. While pre-wiring focuses on when to engage, tailoring focuses on how.

Tailoring your communication means adjusting its style, tone, depth, and format to fit your audience’s level of expertise, decision-making authority, and cultural or organizational context.

Tailoring acknowledges that no message exists in a vacuum. Different audiences require different communication styles. For example, a board of directors expects strategic brevity, a technical team values analytical depth, and a skeptical regulator demands precision and evidence. The same storyline can be conveyed in different ways: a concise elevator pitch, a ten-slide executive briefing, or a detailed technical report. All of these reflect the same logic yet are calibrated for resonance.

Tailoring also involves understanding cultural preferences and interpersonal dynamics. Some decision-makers prefer bold recommendations stated upfront, while others prefer to be led gently through the reasoning before hearing the conclusion. For example, a direct, data-heavy message that works in a U.S. boardroom may feel too blunt in a Japanese context. Likewise, a confident assertion that impresses one CEO may alienate another who prefers to reach conclusions collaboratively. Understanding the audience’s decision-making style, risk tolerance, and communication preferences is part of a professional’s responsibility. Therefore, the communicator must read the room, sense power relationships, and adjust accordingly without compromising the message’s integrity.

Pre-wiring and tailoring reinforce each other. Pre-wiring reveals how different stakeholders think, while tailoring allows communicators to meet those stakeholders where they are. Together, these processes transform communication from a one-way broadcast into a strategic engagement and co-creation process.

10. The Medium and the Message

Although the logic of communication is universal, the medium through which it is delivered shapes how the message is received. In most professional settings, slide decks created with Microsoft PowerPoint or similar software are the default medium of communication. However, this “comfort tool” can be both a blessing and a curse. While it offers structure and visual support, it can also seduce problem solvers into mistaking slides for thinking.

Slides are merely visual representations of structured ideas. The real substance lies in the storyline and logic conveyed by the slides. Therefore, the correct sequence is: first think, then write, then design. When communicators start with the slides, the narrative tends to fragment and the logic weakens. Hence, the proper approach is to develop the storyline first and then design the slides. Once the logical and emotional flow is clear, the visuals can be designed to reinforce the argument. Avoid overdesigned slides, unnecessary animations, and decorative icons. Audiences respect simplicity and substance.

Good slides share several characteristics. They are visually clean and limited to one message per page. They are also anchored by an action title, which is a short sentence that summarizes the main takeaway rather than simply labeling a topic. Every chart or exhibit on the slide must directly support the title. When read in sequence, all titles should recreate the storyline, forming a coherent, top-down narrative.

However, PowerPoint is not the only available medium. For instance, according to Garrette, Phelps & Sibony (2018, p. 246), Amazon prohibits the use of PowerPoint in executive meetings. Instead, presenters write four- to six-page memos called “narratives” that participants read silently before the discussion begins. This format requires depth of reasoning and coherence of structure, which are often destroyed in slide-driven meetings. No matter what you use—slides, memos, or verbal pitches—the principle remains: form must follow thought.

The lesson is timeless: the effectiveness of communication depends more on the discipline of thought behind it than on the medium. Slides, memos, and posters are merely instruments for expressing the pyramid. What matters most are clarity of structure, precision of argument, and respect for the audience’s time.

11. Engaging the Audience

The most common mistake in professional presentations is focusing on the process of the analysis—how the work was done, which methods were used, and what data was gathered. Audiences rarely care about the process. They want to hear about the solution, what the findings mean, and what should be done next.

Effective communication is not a lecture; it is a dialog. After stating your main idea, encourage your audience to think with you instead of just listening to you. Good presenters anticipate the “why” and “how” questions their main idea will provoke and prepare key responses.

To deepen engagement:

- Start strong by opening with a clear, relevant statement of the problem and recommendation.

- Maintain narrative flow by using transitions such as “because,” “therefore,” and “as a result” to guide thinking.

- Use questions: rhetorical or literal questions invite reflection and break monotony.

- Integrate stories and analogies: abstract logic becomes memorable when illustrated by concrete examples.

- Adapt your energy by modulating your tone, pacing, and body language to match audience reactions.

As mentioned above, effective communicators humanize their message. They use analogies, stories, and examples that make complex issues tangible. For example, instead of saying, “Our value chain is fragmented,” one might say, “Our customer journey is like a relay race in which no one knows when to pass the baton.” Such imagery engages the emotions and memory.

However, stories must never replace logic. They illustrate, but they do not substitute for reasoning. Your task is to enlighten and persuade, not to entertain. When telling stories or using analogies, be selective. They should clarify, not distract. A relevant example can anchor complex reasoning, while an irrelevant anecdote can derail it.

Audience engagement also depends on authenticity. Decision-makers can sense when a presenter truly believes in their message. Confidence comes not from performance tricks, but from mastery of the material. When communicators genuinely understand and trust their argument, persuasion comes naturally.

12. Internal Communication and Team Alignment

The problem-solving team must also excel at communication. Open, frequent, and structured internal communication ensures alignment, consistency, and morale. Transparent information sharing enables teams to work faster and with fewer errors.

Regular meetings with clear agendas, coupled with informal “management by walking around,” foster trust and cohesion. Every team member must understand not only their task, but also the project’s evolving storyline, so they can speak with one voice when engaging stakeholders.

Strong external communication begins with strong internal communication. The quality of dialog within problem-solving teams determines the coherence of their thinking and the credibility of their output. Even a brilliant analysis can quickly lose its persuasive power if it is presented inconsistently by team members.

Internal communication serves three interconnected purposes: coordination, coherence, and culture. Coordination ensures that everyone knows what others are doing, coherence ensures that the parts fit together into one storyline, and culture ensures that people feel psychologically safe enough to share ideas and challenge assumptions.

12.1 Maintaining a Shared “North Star”

Every team should be united around a single North Star: the current version of the overarching idea. From the hypothesis stage to the final synthesis, every team member—from the junior analyst to the project lead—should be able to articulate the main idea in one or two sentences. Regular check-ins that ask, “Has our key message changed?” help keep the team aligned and aware of shifts in understanding.

These meetings should focus not only on tasks and timelines, but also on narrative alignment. Revisiting the storyline as evidence evolves prevents “analysis drift” that can fragment teams and produce inconsistent messages.

12.2 Balancing Formal and Informal Communication

High-performing teams balance formal channels, such as scheduled meetings, written updates, and structured briefings, with informal conversations that maintain the flow of information between these events. These informal exchanges, such as quick chats, shared notes, and virtual huddles, often reveal insights that formal meetings overlook. Leaders who practice “management by walking around,” or its digital equivalent, can identify emerging problems early and maintain morale.

What matters is rhythm. Communication should be frequent enough to sustain momentum, yet not so constant that it becomes white noise. Clear protocols for sharing drafts, findings, and storyline updates ensure that everyone works from the same version of the truth.

12.3 Communicating Across Roles and Disciplines

Modern problem-solving teams are inherently multidisciplinary. Analysts, strategists, technologists, and client representatives each contribute unique vocabularies and mental models. Misunderstandings often arise not from disagreement, but from translation failure. For example, a data scientist’s “confidence interval” may mean little to a marketing executive, while a strategist’s “positioning statement” may sound vague to a quant.

Leaders must act as translators, ensuring that insights are expressed in a language everyone can understand. This cross-disciplinary interpretation enhances collective intelligence and produces solutions that are rigorous yet practical.

12.4 Creating Feedback Loops

Effective teams institutionalize two-way feedback. Information must flow upward and laterally, not just downward. Junior team members who perform detailed analyses often detect inconsistencies before anyone else. Encouraging them to voice their concerns improves accuracy and builds trust.

Some teams formalize this process through “red team” reviews—sessions in which one subgroup deliberately challenges the assumptions and logic of another. These exercises normalize constructive critique and strengthen the eventual storyline and are far from being confrontational.

12.5 Aligning on the External Message

Before any external communication, such as a client presentation, stakeholder briefing, or executive summary, the team must agree on the content and tone. Disagreement in delivery can undermine weeks of excellent analysis. A brief rehearsal in which each participant summarizes the main message helps identify inconsistencies.

One-voice alignment ensures that all team members communicate the same governing thought and storyline externally. When asked to summarize the recommendation independently, their answers should converge. Consistency in message and tone signals coherence, professionalism, and unity.

Teams can use simple yet effective techniques to achieve one-voice alignment. These techniques include jointly revising the executive summary, reading slide titles aloud in order, and conducting mock Q&A sessions. These techniques ensure a shared understanding.

12.6 The Cultural Dimension

Finally, internal communication reflects culture. Teams that value openness and respect foster an environment of intellectual honesty, where members feel comfortable admitting uncertainty, proposing alternatives, and challenging assumptions. These types of environments foster learning and innovation.

In contrast, teams that equate dissent with disloyalty or hoard information create an environment of fear and rigidity. Therefore, strong team communication requires not only a process, but also psychological safety—a culture in which curiosity and constructive disagreement are signs of commitment, not rebellion.

When internal communication functions well, it becomes a rehearsal for the external performance. The team speaks with one voice, not because dissent is suppressed, but because understanding is shared.

13. The Discipline of “Good Enough”

Perfectionism is a common professional hazard in high-performance environments. Thus, effective communication requires discipline. Many professionals, especially consultants and analysts, fall into the trap of endless refinement. They often spend excessive amounts of time perfecting slides or rephrasing titles, even after the argument has been established. They polish slides late into the night, adjusting fonts and word spacing in pursuit of perfection. The result is diminishing returns—and sometimes exhaustion. In practice, however, the effectiveness of communication depends less on cosmetic details and more on mental clarity and confident delivery.

Like analysis, communication follows the law of diminishing marginal value. Once clarity, accuracy, and logical consistency are achieved, further refinements rarely enhance persuasiveness. In fact, further refinements can weaken delivery by consuming time and energy that should be spent rehearsing or engaging with stakeholders.

Hence, top-tier consulting firms teach their new associates an important lesson: the marginal returns on late-night perfectionism are negative. A crisp, well-structured, and confidently delivered presentation beats a visually perfect but incoherent one every time. Clarity, brevity, and presence of mind are the hallmarks of mastery.

The discipline of “good enough” does not mean settling for mediocrity. Rather, it means recognizing the point at which additional effort no longer changes the audience’s decision. Professional communicators stop perfecting form once the substance is sound. They focus on delivery instead—the energy, empathy, and presence that bring the story to life.

As the writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry said (AsayQ Technology & Automation Systems 2025): “Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to remove.” Clarity, brevity, and presence of mind are the hallmarks of mastery.

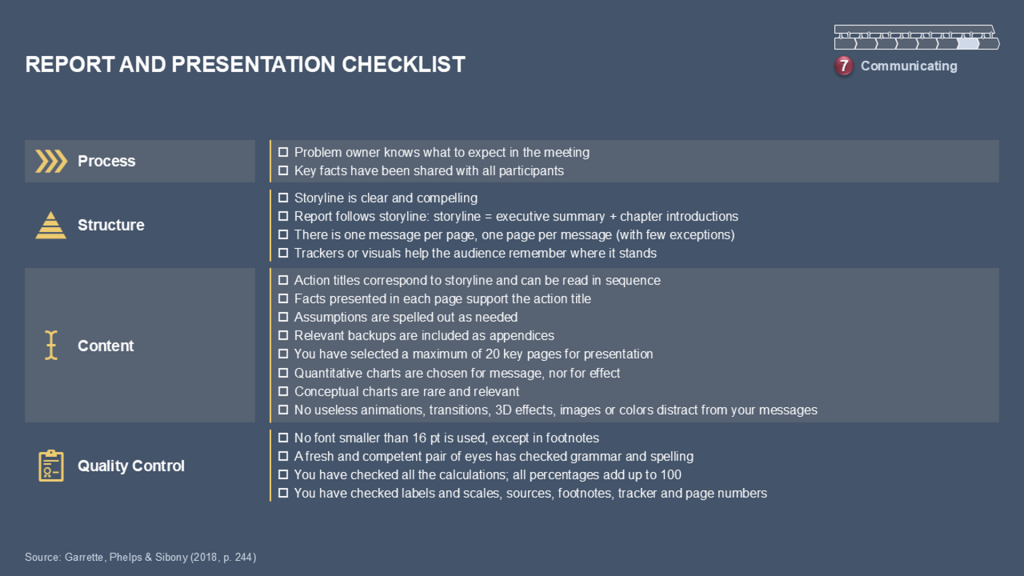

14. Report and Presentation Checklist

Even the most elegant storyline and visuals can fall short if the details of execution are overlooked. Before sharing a report or delivering a presentation, professionals should perform one final quality and coherence check. Exhibit 9 provides a concise report and presentation checklist that encapsulates the essential processes, structures, contents, and quality standards discussed throughout this elaborations. This checklist helps ensure that communication is intellectually sound and visually disciplined, polished, and audience-ready—clear, credible, and “good enough” to make an impact.

15. Key Takeaways

- Communication transforms insight into action. Without communication, even the best solution remains inert.

- Start with the governing thought. Clearly and confidently state your recommendation first.

- Use the Pyramid Principle to structure your message logically and hierarchically.

- Blend inductive and deductive logic to combine evidence and reasoning.

- Build a MECE storyline before creating any visuals.

- Choose between grouping and argument patterns depending on the audience’s mindset.

- Manage the process proactively through pre-wiring and tailoring.

- Tailor the message to the audience’s knowledge, preferences, and decision-making authority.

- Slides are tools, not substance. The storyline must precede design.

- Engage in dialog, not monolog. Invite reflection, not passive listening.

- Foster internal communication to keep your team aligned and credible.

- Aim for disciplined sufficiency, not perfectionism. The goal is persuasion, not artistry.

References

AsayQ Technology & Automation Systems (2025) aSAY Q® – KNX Multi Actuator 24 Outputs – 12 Digital Inputs Lighting, Curtain, Blind, Heating, and FanCoil Control. Accessed October 11, 2025, https://www.asayq.com.tr/en/asay-q-knx-multi-actuator-24-outputs-12-digital-inputs-lighting-curtain-blind-heating-and-fancoil-control/.

Conn C, McLean R (2018) Bulletproof Problem Solving (Wiley, Hoboken, NJ).

Minto, B (2009) The Pyramid Principle: Logic in Writing and Thinking (Harlow, United Kingdom).

Garrette B, Phelps C, Sibony O (2018) Cracked it! How to Solve Big Problems and Sell Solutions Like Top Strategy Consultants (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, Switzerland).