Building Project Leadership at Scale: Why a New, Capability‑Based Training Program Is Needed Now

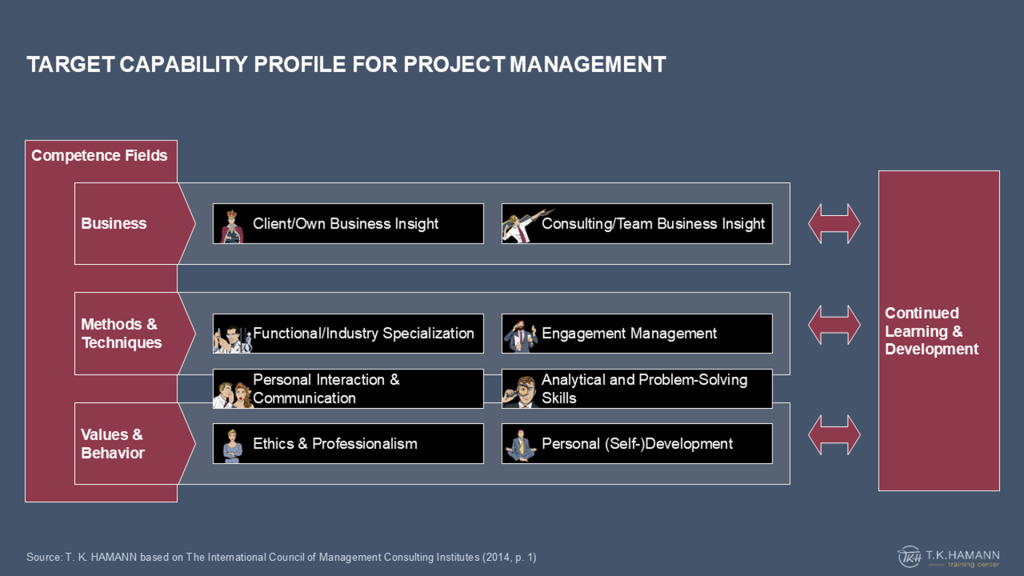

Although project work has become the dominant engine of value creation, too many initiatives still miss deadlines, exceed budgets, or fail to deliver promised benefits. The demand for project talent is growing faster than organizations can develop it, and the most common development routes—degrees and certifications—do not reliably build the applied capabilities required for real projects. A new training program that adopts the relevant capability profile (see Exhibit) as its foundation and explicitly develops and fairly assesses the full set of professional, analytical, interaction, and delivery competencies associated with consistent project success is warranted. In short, the problem is structural, the capability gaps are measurable, and the solution must focus on building capabilities rather than on the syllabus.

1. The Strategic Imperative

Today’s portfolio is shaped by two secular trends: the “projectification” of work and the persistently low success rates of projects. Survey and macroeconomic evidence indicate significant growth in projects and project-related employment. For instance, a national study by GPM Deutsche Gesellschaft für Projektmanagement (2023, p. 9) found that 34.5 percent of work time in Germany is currently spent on projects. Additionally, the Project Management Institute (2021, p. 4; 2022, p. 3) anticipates an additional 25 million project workers worldwide by 2030. Organizations are shifting their structure from line activities to project-shaped initiatives, using them not only for transformation but also for core business operations. The result is sustained, systemic demand for project-ready talent that the traditional pipeline cannot supply.

Against this backdrop, outcomes remain discouraging. Meta-surveys (e.g., The Standish Group 2015; Johnson 2020 as cited in Portmann 2021) report that only a minority of projects are delivered on time, on budget, and with the intended benefits. In one cross-industry sample (KPMG, the Australian Institute of Project Management, and the International Management Association 2019), only 19 percent of organizations successfully complete projects most of the time. Meanwhile, schedule, budget, stakeholder satisfaction, and benefit attainment lag far behind aspirations. Large business transformations underperform at even higher rates (Spencer & Watkins 2019, Burke 2024). These are not isolated “bad luck” events; they are pattern failures.

The root cause is more about capabilities than tools. Recurrent failure drivers, such as weak scoping, poor stakeholder alignment, shallow problem framing, brittle governance, and limited benefits thinking, map directly to missing competencies rather than a lack of templates. At the same time, employers describe a widespread lack of applied skills in critical thinking, analysis, project management, communication, and resilience (Society for Human Resource Management 2016; QS Quacquarelli Symonds 2023)—the very skills projects require. Therefore, the supply of project-ready talent structurally lags demand.

2. Why Existing Development Pathways Do Not Close the Gap

Although academic degrees build valuable literacy, they rarely provide enough supervised, feedback-rich practice in delivering complex projects under real constraints. Even when capstones exist, assessments often rely on papers and classroom assignments that reward recall and neat analysis more than live stakeholder work and iterative problem solving. This discrepancy between what is taught and what projects require helps explain the persistent delivery gap.

Certifications provide market signaling and a shared vocabulary. They demand relatively modest learning time and are primarily assessed through written examinations. As our analysis shows, a typical Project Management Professional (PMP)® candidate spends about 105 hours preparing (including working through exam questions), which is orders of magnitude less time than graduates of rigorous programs spend building and applying skills (T. K. HAMANN training center 2025a). Furthermore, the exam’s focus and item types tend to be at lower taxonomy levels, such as knowing and recognizing rather than diagnosing, synthesizing, and creating (T. K. HAMANN training center 2025b). This limits the predictive validity of performance in messy, real-world settings. Various studies (e.g., Nazeer & Marnewick 2018; Dehghanpour Farashah, Thomas & Blomquist 2019) find no empirical links between certification alone and improved delivery outcomes.

In contrast, the top-tier consulting apprenticeship program combines structured training, coached practice, and rigorous review cycles on live projects. This approach is widely regarded as the most reliable way to develop the integrated skill set that projects require: framing, analysis, influencing, disciplined execution, and benefits realization. However, it is scarce: the number of alumni is small relative to the demand across the entire economy, and firms cannot serve as the sole training system for every sector. The lesson is not to “hire all consultants,” but rather to adopt the developmental strategies of apprenticeships, case-to-real transfer, and rubric-based reviews for the broader workforce.

3. What “Good” Looks Like: The Target Capability Profile for Project Management

The Exhibit presents the target capability profile, which provides a practical definition of the competencies associated with reliable project performance. It spans eight elements across three competence fields. In the Values & Behavior competence field are Ethics and Professionalism and Personal (Self-)Development. The Methods & Techniques competence field includes Functional/Industry Specialization and Engagement Management. Since personal interaction and analytical/problem-solving skills have behavioral, and technical and methodical aspects, these elements cover facets of both respective competence fields. Additionally, the capability profile contains a Business competence field. This is because effective consultants and project managers must understand the businesses of their clients or their own organizations, as well as the interests of their consulting practices or internal project teams. All capabilities in these eight areas must be expanded and kept up to date through continued learning and development efforts.

Together, these fields describe the full stack, including how people conduct themselves, frame and solve problems, interact and influence, plan, govern, deliver, and keep learning. This profile is specific enough to anchor learning goals and assessment rubrics, yet flexible enough to apply across industries and methodologies (agile, hybrid, or plan-driven). Using this profile as the program’s backbone establishes a shared language for expectations, development, and promotion.

4. Why a New Program Built on That Profile Is Necessary

The evidence base points to a simple yet powerful conclusion: closing the project delivery gap requires building capabilities, not just knowledge. Therefore, a credible program should be outcomes-first. Start with explicit performance standards for each field in the capability profile and require learners to demonstrate those standards in authentic work, rather than just describing them on paper. In practice, this means blending concise instruction with coached application on live initiatives and evaluating progress through rubric-based reviews modeled on the engagement performance assessments used by elite apprenticeship systems. These reviews emphasize higher-level thinking skills, such as applying, analyzing, synthesizing, evaluating, and creating new approaches, rather than memorization.

A program like this must differ from a curriculum catalog. First, it needs to be a performance system that clarifies what “good” looks like through the capability profile. Second, it must create repeated, coached opportunities to practice. Third, it must measure actual contributions to project outcomes. The program must address the market’s documented gaps in project management, analysis, communication, and problem-solving skills by incorporating these competencies into daily operations instead of treating them as abstract concepts in a classroom. Organizations that adopt this capability-led approach can expect fewer rework loops, tighter schedules and budgets, and better realization of benefits because the people doing the work will have practiced, received coaching, and been held accountable for what matters.

5. Risks of Inaction (and the Business Rationale)

Without a capability-based training system, two costs compound every month: portfolio underperformance and talent churn. Underperforming projects either defer or destroy value, and overstretched teams facing ambiguous expectations either burn out or leave. Conversely, modest improvements in schedule adherence and benefit attainment applied across a portfolio overwhelm the fixed cost of a focused capability program. Therefore, the “why now” is not only strategic (moving at the pace of change), but also financial (protecting and unlocking value already planned into the portfolio).

6. Recommendation

Adopt the Capability Profile as the enterprise standard for project roles and authorize the design of a capability-based training program that uses the profile to:

- Set transparent standards

- Coach people while they deliver

- Evaluate performance using meaningful rubrics

This is the most direct, evidence-supported way to improve delivery on a large scale without relying on scarce external apprenticeship markets. The alternative—continuing to invest primarily in content hours and examinations—has been tried at scale and has fallen short.

References

Burke M (2024) 88% of business transformations fail to achieve their original ambitions; those that succeed avoid overloading top talent. Press release (April 15), Bain & Company, Boston, MA. Accessed January 24, 2025, https://www.bain.com/about/media-center/press-releases/2024/88-of-business-transformations-fail-to-achieve-their-original-ambitions-those-that-succeed-avoid-overloading-top-talent/.

Dehghanpour Farashah A, Thomas J, Blomquist T (2019) Exploring the value of project management certification in selection and recruiting. International Journal of Project Management 37(1):14–26.

GPM Deutsche Gesellschaft für Projektmanagement (2023) Projektifizierung 2.0: Zweite Makroökonomische Vermessung der Projekttätigkeit in Deutschland [Projectification 2.0: Second Macroeconomic Survey of Project Activity in Germany] (UVK Verlag, Munich, Germany).

Johnson J (2020) CHAOS report: Beyond infinity. Report, The Standish Group, Centerville, MA.

KPMG, Australian Institute of Project Management (AIPM), International Project Management Association (IPMA) (2019) The future of project management: Global outlook 2019. Report, KPMG, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Nazeer J, Marnewick C (2018) Investing in project management certification: Do organisations get their money’s worth? Information Technology and Management 19(1):51–74.

Nieto-Rodriguez A (2022) Das Zeitalter der Projekte [The era of projects]. Harvard Business manager 44(2):21–29.

Portman H (2021) Review Standish Group – CHAOS 2020: Beyond infinity. Blog, Henny Portman, Randstad, the Netherlands. Accessed October 20, 2022, https://hennyportman.wordpress.com/2021/01/06/review-standish-group-chaos-2020-beyond-infinity/.

Project Management Institute (PMI) (2021) Talent gap: Ten-year employment trends, costs, and global implications. Report, Global Headquarters, Project Management Institute, Newton Square, PA.

Project Management Institute (PMI) (2022) 2022 jobs report: Opportunity amid recovery. Report, Global Headquarters, Project Management Institute, Newton Square, PA.

QS Quacquarelli Symonds (2023) The skills gap: What employers want from business school graduates. Report, QS Quacquarelli Symonds, London, United Kingdom.

Society for Human Resource Management (2016) The new talent landscape: Recruiting difficulty and skills shortages. Report, Society for Human Resource Management, Alexandria, VA.

Spencer J, Watkins M (2019) Why organizational change fails. Accessed February 20, 2023, https://www.tlnt.com/why-organizational-change-fails/.

The International Council of Management Consulting Institutes (ICMCI) (2014) CMC certification scheme manual: appendix 1 – CMC® competence framework. Manual, CMC-Global, ICMCI, Zurich, Switzerland.

The Standish Group (2015) CHAOS report 2015. Report, The Standish Group, Centerville, MA. Accessed October 20, 2022, https://www.standishgroup.com/sample_research_files/CHAOSReport2015-Final.pdf.

T. K. HAMANN training center (2025a) At top-tier consulting firms, project management training is far superior to corresponding academic degrees or certifications. Blog, T. K. HAMANN training center, Munich, Germany. Accessed November 07, 2025, https://tkhamann.training/blogpost_no-21/.

T. K. HAMANN training center (2025b) The PMI-PMP® exam has the lowest cognitive demands, while project management trainees at top-tier consultancies and academic degree programs must demonstrate the highest. Blog, T. K. HAMANN training center, Munich, Germany. Accessed November 07, 2025, https://tkhamann.training/blogpost_no-23/.