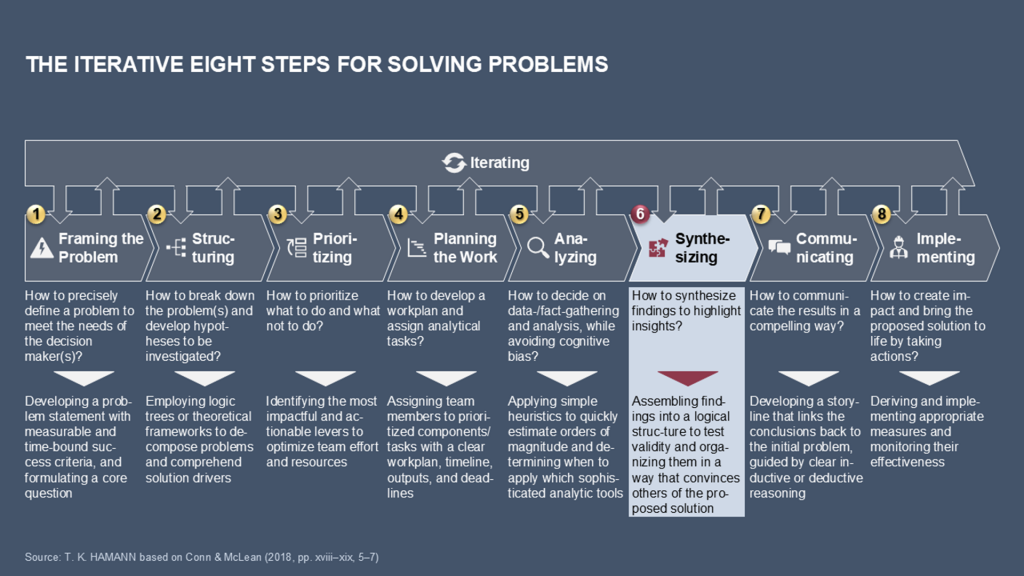

The Iterative Eight Steps for Solving Problems – Step 6: Synthesizing

In the Iterative Eight Steps for solving problems, synthesizing naturally follows the analytical work of step five (see Exhibit 1). By this point, the problem has been carefully defined and broken down into logical structures. It has also been prioritized and the analytical work has been planned and executed. Now, problem solvers face not the absence of evidence, but its abundance. There may be dozens of charts, numbers, interview notes, and calculations—yet none of them, on their own, provides a solution. The task of this sixth step is to assemble, integrate, and interpret. This is what we call synthesizing. It is the process of distilling many analyses into a few powerful insights that explain the problem, point toward solutions, and prepare the ground for action. In essence, synthesizing is where the intellectual raw material of problem solving is transformed into clarity and direction.

Synthesizing is the process of assembling and integrating findings from analyses into a coherent structure that highlights insights, builds arguments, and prepares the ground for clear communication and decision making.

1. Why Synthesizing Matters

Organizations and leaders are not interested in raw data tables, endless charts, or sophisticated models for their own sake. They are interested in the implications and answers to questions such as: “What does this mean?” “What should we do?” “How can we move forward?” Without synthesis, analysis remains fragmented, which can overwhelm or mislead stakeholders. With synthesis, however, complexity is distilled into clarity, and the path forward becomes actionable.

There are several reasons why synthesizing matters and is so critical:

- It connects the pieces:

Individual analyses often remain confined to narrow branches of the problem tree. Synthesis links these findings to create an overall picture. So, it allows teams to see the big picture by connecting different analyses into a coherent view of the overall problem. - It creates cross-branch insights:

When evidence from different parts of the problem tree is combined, patterns emerge that were invisible at the branch level. Therefore, synthesis often uncovers insights that cut across analytical branches—insights invisible when each analysis was considered in isolation. - It provides direction:

Synthesis highlights the most important insights for action, preventing stakeholders from being overwhelmed by details. - It builds the storyline:

Synthesis organizes insights into a narrative, paving the way for communication. It provides the storyline that links the work back to the original problem framing, making the results communicable and actionable. Without synthesis, the problem-solving process risks ending with a pile of interesting yet unusable findings.

An insight is a deep understanding that goes beyond facts and identifies underlying drivers, implications, or opportunities for action.

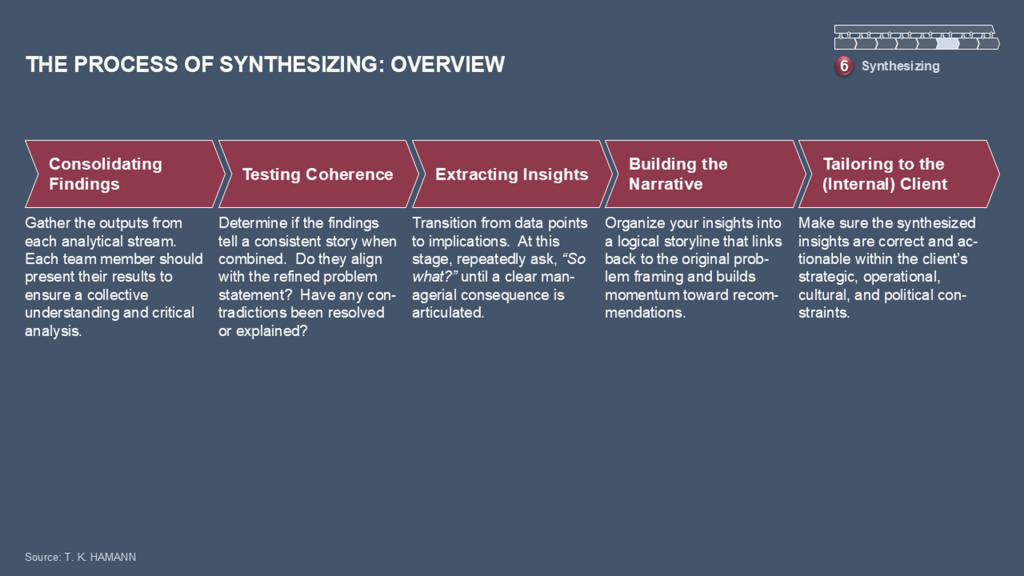

2. The Process of Synthesizing

Synthesizing can be viewed as a multi-stage journey. Each stage requires disciplined reasoning and creative interpretation.

- Step 1: Consolidating Findings

The process begins by bringing together all the analysis outputs. The team then assembles the data, models, and interview insights in one place. It is important to note that this stage is not yet about interpretation; it is about ensuring that nothing valuable is overlooked. - Step 2: Testing Coherence

Next, the findings are checked for coherence. Do they support or contradict each other? Are there any gaps or inconsistencies? Often, this stage requires revisiting earlier hypotheses and discarding analyses that led to dead ends. - Step 3: Extracting Insights

Here, the team transitions from “What does the data say?” to “What does the data mean?” The key question is always: “So what?” If an analysis cannot answer this question, then it may be irrelevant to the final storyline. At this point, correlations are tested for causation, contradictions are explained, and the first seeds of recommendations emerge. - Step 4: Building the Narrative

Once the insights have been identified, they must be organized into a coherent storyline. Rather than a random list of findings, it should be a structured sequence that flows logically from problem definition to solution. The narrative serves as a communication bridge. - Step 5: Tailoring to the Client

Finally, the synthesized narrative must be tested against the reality of the client or organization. Even the most elegant solution is useless if it cannot be implemented. Therefore, the synthesized insights should reflect analytical truth and practical feasibility.

Exhibit 2 summarizes the different stages.

3. Tools and Techniques for Synthesizing

Synthesizing is not purely an art. Several proven tools and techniques can guide the process and strengthen insights. One stands out as particularly central: the one-day answer, which is often structured through the SCQA framework.

3.1 The One-Day Answer and SCQA

The one-day answer concept emphasizes that synthesis begins on day one, not at the end of a project. Even before analyses are complete, teams develop a preliminary explanation of the problem and its solution. This provisional answer provides direction and focus while allowing for refinement.

The one-day answer is often expressed through the SCQA structure:

- Situation:

“What is the current state of affairs?” This establishes the baseline. - Complication:

“What about the situation is problematic or unsustainable?” The complication creates tension and emphasizes the importance of the situation. - Question:

“What central issue must be resolved to move forward?” This clarifies the problem statement. - Answer:

“What is the best hypothesis for resolving the issue?” Though initially tentative, this answer becomes more robust through analysis and synthesis.

This structure is powerful because it aligns with the way humans naturally process information. It helps teams develop initial hypotheses, test them against evidence, and refine them until a final storyline emerges.

3.2 Logic Trees and Visual Maps

Visualizing the findings on the original problem tree reveals which branches are supported and weak and how they fit together. Revised logic trees demonstrate the evolution from raw data to integrated insight.

3.3 The 80/20 Rule

The Pareto principle serves as a constant reminder during synthesis that not every analysis is equally valuable. Teams should focus on the 20 percent of findings that explain and drive 80 percent of the problem and solution.

3.4 Collaborative Synthesis Sessions

Top-performing teams often hold joint synthesis workshops, during which each team member presents their results and the group integrates them collectively. These sessions test alternative hypotheses, reveal blind spots, and foster shared responsibility for the conclusions.

3.5 Visualization and Storyboarding

Since humans are visual learners, charts, graphs, and storyboards often provide insights that text alone cannot. In particular, storyboards allow teams to plan out the storyline before deciding on a final communication format.

4. Preparing the Ground for Communication

Synthesis is not an end in itself. Its purpose is to prepare the way for communication with decision-makers. Once findings are organized into insights and a narrative, the team is ready to craft a convincing and motivating message.

In this context, Barbara Minto’s (2009) Pyramid Principle becomes highly relevant. It provides a rigorous way of structuring communication so that recommendations are logical, hierarchical, and persuasive. Although this principle belongs to the next step of the Iterative Eight, Communicating, its relevance begins in synthesis because the way findings are structured now determines how effectively they can be communicated later.

5. Conclusion and Outlook

Synthesis is the turning point of the problem-solving process. It transforms fragmented analyses into integrated insights, links findings back to the problem definition, and simplifies complexity. Problem solvers create a storyline that is both analytically sound and practically relevant by moving systematically through the stages of consolidation, coherence testing, insight extraction, narrative building, and client adaptation.

Tools such as logic trees, the 80/20 rule, and collaborative workshops support this work. At the heart of synthesis lies the one-day answer, structured through SCQA. SCQA guides reasoning from the beginning and evolves into the final storyline.

However, synthesis alone is insufficient. The most brilliant insight achieves nothing if it cannot be communicated compellingly. Next, we will turn to communication and the Pyramid Principle, a powerful method for structuring communication. This method builds on the foundation of synthesis to ensure that insights resonate with decision-makers.

6. Key Points

- Synthesizing is the disciplined process of transforming analytical findings into meaningful insights.

- This process unfolds in stages: consolidating findings, testing coherence, extracting insights, building the narrative, and tailoring it to the client.

- The one-day answer, structured through the SCQA framework, is a central synthesis tool that helps teams refine their hypotheses iteratively.

- Other tools, such as logic trees, the 80/20 rule, and collaborative synthesis sessions, enhance clarity and robustness.

- Synthesis prepares the ground for effective communication, a topic that will be further explored in the next chapter through Barbara Minto’s (2009) Pyramid Principle.

References

Conn C, McLean R (2018) Bulletproof Problem Solving (Wiley, Hoboken, NJ).

Minto, B (2009) The Pyramid Principle: Logic in Writing and Thinking (Harlow, United Kingdom).